For nearly two centuries, the experiments at Rothamsted Research have offered invaluable insights into the dynamics of soil health, crop yields, and environmental interactions. As agriculture evolves, Rothamsted remains a cornerstone in the pursuit of sustainable farming, helping address the pressing challenges of climate change and food security.

The Classic Experiments are the name of the long-term trials created by Sir John Bennet Lawes and Sir Joseph Henry Gilbert between 1843 and 1856. Though not initially intended as long-term studies, the value of repeating the trials became clear. “The object of these investigations is not exactly to put money into my pocket but to give you the knowledge by which you may be able to put money into yours,” said Sir John Lawes in 1854. One of the most remarkable aspects of Lawes’ and Gilbert’s work was their foresight in retaining samples of crops and soils taken for chemical analysis.

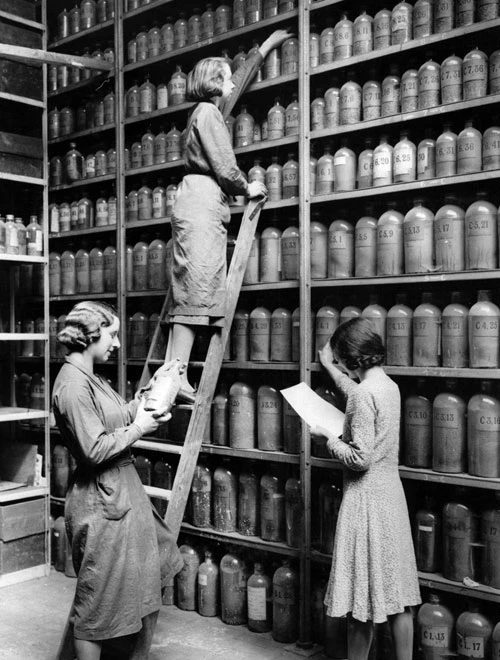

Successive generations of scientists have continued to add to the collection, and today, Rothamsted’s archive contains around 300,000 samples, including oven-dried, ground, and unground plant material as well as soils, manures, and fertilisers applied to experimental plots. The Broadbalk field, which had been in arable use for centuries, saw its first experimental crop of winter wheat sown in 1843 and harvested in 1844. Every year since, wheat has been grown and harvested from the same field, a testament to long-term research continuity.

Rothamsted during the war

Despite staffing shortages, the trials continued unchanged during both World Wars. The farm manager’s wife took over during his call-up and reportedly became the first to run it at a profit. Resourcefulness was key – when glass was unavailable for storing samples, staff brought tins from home. Even under such pressure, Rothamsted continued to provide crucial data. Dr Andy Gregory, head of the Rothamsted long-term experiments, reflects on the importance of these historic trials. “I’ve been at Rothamsted for just over 20 years now, and I continue to see how the trials affect our understanding of current agricultural challenges, and how they lay the groundwork for solutions to problems we haven’t experienced yet,” he says.

What the trials look at

The trials were initially designed to investigate how different nutrients affect crop growth. This involved testing nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium individually and in various combinations. Nitrogen, in particular, was applied at different rates using inorganic forms. Each trial also included a control plot (no inputs) and another that received farmyard manure, offering valuable comparisons over time. A distinctive feature of these trials, introduced by Lawes and Bennet, was growing the same crop year after year. While not common in 19th-century agriculture, they deliberately adopted this approach, believing it was the most effective way to understand and precisely determine the long-term nutrient requirements of crops.

“Since Lawes’ death, there have been modifications, such as more plots added to Broadbalk to test the effects of P in the presence of N, K, Na, and Mg,” explains Andy. “Chalk has been applied intermittently since the 1950s to maintain pH at a level at which crop yield is unaffected. It was not until the First World War that the experiment was hand weeded, but the labour shortage allowed weed competition to become so severe that yields declined by the 1920s. To control these weeds, the experiment was divided into five sections, with one section bare fallowed each year, and the yields recovered.”

Since 1964, herbicides have been used on all the plots, except for half of one section where weeds are allowed to grow unless fallowing becomes necessary. The current wheat variety is in its sixth and final year of cultivation, a practice that aligns with the typical six-harvest cycle before a change is made. This autumn, it will be replaced by a new variety from the AHDB Recommended List, reflecting what’s currently a popular choice for farmers. This new variety is a collaborative decision made by a committee that includes scientists, agronomists, and farm staff.

Long-term data opens doors

“The wheat is always a bread-making wheat, something which has good disease resistance, and something that we’re confident we can get the seeds for the next five years,” explains Andy. “This highlights the key priorities in their selection process: Ensuring the wheat is suitable for bread production, resilient against common diseases, and consistently available for future planting. As new technology continues transforming agriculture, Andy highlights a significant development in how Rothamsted monitors soil. “There are new non-destructive ways to test soil being introduced through sensors, but more work is still needed before it completely replaces traditional chemistry-based methods.”

This indicates an exciting shift toward more efficient and less invasive soil analysis, though traditional techniques remain essential. Rothamsted’s long-term data opens doors for unexpected discoveries. “One student contacted us as he knew we had soil from before the plastic era; he was able to show convincingly the accumulation of microplastics in recent decades in the plots where we use inorganic fertiliser and manure, but there was also accumulation under the nil plot as well,” explains Andy.

Climate-changing weather patterns

“There’s no doubt that climate change is affecting our weather,” he adds. “Lawes first started collecting rainwater during the 1850s, and we’ve had air temperature data since the 1870s.” A student’s research recently underscored the significance of these long-term records. “He could identify about 10 different weather patterns and see that some which were more common in the 19th and early 20th century are less common now.” This research powerfully demonstrates how Rothamsted’s extensive historical datasets are crucial for identifying and understanding the real-world impacts of climate change on agricultural patterns.

I don’t know how the data I’m collecting will be used. It could be 100 years from now.

Dr Andy Gregory, Head of Rothamsted

Future of Rothemsted

While the future of Rothamsted remains open-ended, the spirit of discovery endures. “Without knowing exactly what will happen, I think we can be confident that things will change, and new things will be measured, and they will be used in new ways, based anecdotally on what’s happened so far.” Rothamsted’s long-term trials are an irreplaceable global asset, providing continuous, invaluable data that transcends immediate applications. “One thing about the classical experiment trials, which I find fascinating, is that I don’t know where the data I’m collecting could be used,” notes Andy. “It could be another 100 years from now until they are used to their full potential.”