With an almost imperceptible nudge of the joystick, 4,500hp of tugboat muscle revs quietly as Captain Steve Coles lines up the Ryan Point with an anchored barge. The new tugboat is the pride and joy of the transport company Tidewater, as it was designed to be able to turn on the spot. Mr Coles, who has spent 38 years on the Columbia River, controls the boat with ease. It requires both power and a light touch to master these waters as they rush towards the Pacific at 8.5m litres/second.

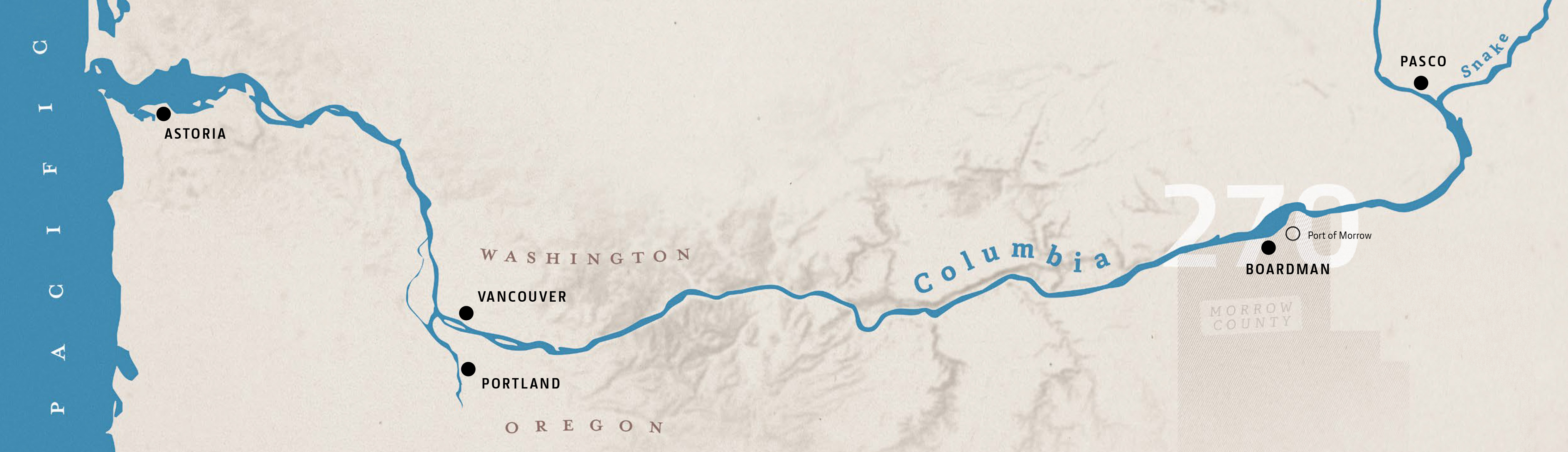

Mr Coles and his four-person crew have already picked up two barges carrying 3,000t of grain each in Pasco, Washington and brought an empty natural gas barge to Pacific Ethanol in Boardman, Oregon (see map). A few yards further downstream, they are picking up a barge of empty steel containers that carry Vancouver, Washington’s solid waste to a landfill site on the other side of Boardman. Freight trains stretching for miles transport grain from North and South Dakota, potash from the Prairies and even Ford cars from Detroit to ports in the North West Pacific region for export. The trains may reach their destination long before Mr Cole’s ship does, but he only needs about one litre of diesel per tonne of wheat to get the tugboat the 170 miles from Boardman to Portland.

The Ryan Point enters the port of Morrow to pick up a barge loaded with wheat.

Downstream from Boardman, the Ryan Point will pass through three of the five dams on the Columbia River, past hydroelectric turbines that used to supply the area’s aluminum smelters and aircraft factories with electricity during World War II. Now they supply energy to enormous server banks by the river to keep the internet working and the digital world moving along.

Gazing through his window nine metres above the surface of the water, Mr Coles looks out on the khaki-coloured hills of Morrow County, Oregon. Along the horizon are the circular sprinkler systems that draw 1% of the Columbia’s water to transform the desert into a fertile land for growing potatoes, onions, mint, vegetables and alfalfa. Behind him, on the north bank, vineyards cling to the steep slopes.

This place, also known as “River Mile 270”, is roughly in the middle of the almost 465-mile (750km) long Columbia River system (which includes its largest tributary, the Snake River). It is a microcosm of everything that makes American rivers and the landscape around them so magnificent, fascinating, and yet challenging. On the river there are boats, barges, fishing skiffs and speedboats. This region not only grows agricultural crops, it processes and ships them too. Data is stored and of course, livings are earned.

Highly diverse

The Port of Morrow is incredibly diverse, according to Kristin Meira, executive director of the Pacific Northwest Waterways Association. “They are not doing a little of everything. They’re doing a lot of everything.” A plethora of different companies processing everything from potatoes to cheese to data have established themselves here in a 3,200ha area on a network of roads, railways, pipelines and powerlines. Alongside a conventional power plant that converts natural gas into electricity, one of the companies is experimenting with biofuel, while another is distilling corn grown in the Midwest into ethanol. Together with the port, these companies pay out around US$500m (£383m) in wages every year to more than 8,400 employees.

Gary Neal, the port’s general manager, points out that Morrow boasts the third-highest average income anywhere in Oregon. Something that could help Boardman and the other neighboring communities to hold on to the next generation through challenging and well-paid jobs. “You don’t need to move to a metropolitan area to get a job in tech,” Mr Neal says. For electricians, lab technicians, plant technicians and other technical professions, the region around Boardman – which has been isolated for so long – is now a popular place to come and work.

Strategic location

Kevin Gray

Just 12 to 18 hours by barge from the export terminals around Portland, mile 270 is also a strategic place to be. “The river gives us just a great transportation tool that’s safe, it’s reliable, and it does such a great job in helping us get the crop out of the interior and into the export channels,” says Kevin Gray, general manager of the local agricultural co-operative, Morrow County Grain Growers. Both red and white wheat is transported from a 60-mile radius to the river, and is eventually exported, primarily to Asia.

The river gives us just a great transportation tool that’s safe and reliable.

Kevin Gray

The agricultural co-operative can store up to 27,000t of grain at the Port of Morrow and has already laid the groundwork to expand a further 16,000t. This will make it possible to transport maize from freight trains in the Midwest and load it directly onto barges.

Next door to the Morrow County Grain Growers, Pacific Ethanol unloads a train of Midwestern maize every 10 days, says manager Daniel Koch. The company distills this into biofuel and ships it to refineries in Portland by barge. Every day, 25 truckloads of wet distillers’ grains supply feed to around 100,000 cattle in a 50-mile radius of Boardman and corn oil is trucked to poultry farms in Oregon and Utah. The efficient transport of maize and ethanol, as well as the region’s bustling buyer market for by-products are crucial reasons to minimise the carbon intensity, Mr Koch notes.

Irrigation lifeline

Thanks to the irrigation lines that transport the river water to farmland, a successful potato and vegetable industry has been established in the Columbia Basin. Farmer Jake Madison from Echo, Oregon says water is the difference between producing a US$250 (£191) dryland wheat crop every other year and harvesting vegetables and onions that can gross US$14,820/ha (£11,347/ha).

The lifeline that ensures Madison’s bountiful harvests is a 20m long pipeline and canal system that transports the river water to his farm. Applied sparingly using 86 centre pivots and other irrigation systems, he is able to optimally divide the water between his fields.

Farmer Jake Madison from Echo diverts river water through a sophisticated irrigation system to his fields to supplement the annual rainfall of around 178 mm.

Since his father secured the last unrestricted water rights to get access to the Columbia in the 1990s, the Madisons have been refining the farm’s water conservation programme. Mr Madison explains that the yield potential of each crop is analysed, along with the amount of water needed to achieve this. Seeding populations, fertilisers and watering schedules are optimised to make the most of the water available.

Jake Madison

Technology takes care of the of the rest. Real-time neutron moisture probes, drop tubes on the pivots, and pressure regulators have significantly reduced water consumption. Today Mr Madison consumes just over half of the total water used when the farm first started irrigating. “We can actually grow better quality crops with less runoff,” he explains.

We can actually grow better quality crops with less runoff.

Jake Madison

Mr Madison’s operation also plays a key role in the port’s environmental sustainability and local agricultural economy. He is among a number of others who are using partially treated industrial water from the port’s industrial plants to supplement his irrigation rights on non-vegetable crops. “It’s got a pretty good nitrogen load to it and it’s liquid, so we can grow crops on it,” he says. “It’s a least-cost alternative to having them just treat it and dump it back in the river. With this additional water and nutrient supply, we can continue with our crop rotation and even expand it.”

Favourable climate and soil conditions in the Columbia River valley make the grapes develop a unique flavour.

In total, the water from the port is spread across about 4,856ha, making it one of the largest areas in the country to take advantage of industrial water in this way, and at the same time be of enormous benefit to the regional agriculture. “When you have a region that gets about 180mm of annual precipitation, most places really need the water for irrigation anyway,” Mr Neal says.

Ideal location for vineyards

The Columbia River has always transported much more than just freight. Thanks to the soil deposits left by glaciers, the floods that formed the course of the river, and the wind that follows the river inland, the region’s wine cultivation is really booming. Winemaker Brittany Komm at Precept Wine says that the grapes on the north bank of River Mile 270 make excellent wine that strongly reflects the local conditions.

“The river is the reason this is such a great growing site,” she says. “We are warm-to-hot in the summer. Around harvest, we cool down just enough to allow for extended hang time, which lets the grapes develop flavour, colour, and sugar.” According to Ms Komm, the wind blows in an ideal direction up for the vineyards, so the grapes get thick skins that give deep, dark colors and a lot of tannins.

Back in Boardman, the port operator and its tenants decided to share the local features of interest with the public and carry out professional marketing. They created the SAGE Centre (Sustainable Agriculture and Energy), that is a magnet for more than 20,000 visitors annually, with exhibits ranging from a French fry processing to scale models of barges.

The visitors are fascinated by the Tidewater exhibit, which highlights the efficiency of barges. A four-barge tow can transport 12,500t of grain – the equivalent of 140 rail cars or almost 500 trucks – with fewer accidents and lower emissions. “We move between 3m and 3.3m tonnes of grain a year,” says Bruce Reed, COO of the shipping company Tidewater. “If all that grain had to move on another mode of transportation, it would certainly clog up the highways.”

Columbia River: North America’s third-largest grain transport corridor

The Columbia River flows through the Pacific Northwest of the USA, ie the states of Washington and Oregon. Its source is further north, in the Canadian province of British Columbia. The Columbia River meets the Pacific at Astoria, Oregon. It is one of just three rivers that manage to break through the coastal mountain range on the North American Pacific coast. For this reason, it is a vital connection from the Continent’s interior to the Pacific coast. With a discharge of around 8.5m litres/second, the Columbia River is the largest river in North America by discharge volume that flows into the Pacific.