The harvester ploughs through a field full of ripe tomatoes with astonishing precision. Sat behind the wheel, Marco Franzoni glances back and forth between his rear-view mirrors, displays and conveyor belts, adjusting the speed of the harvester’s feed and the conveyor belts with levers and knobs as he goes. Ahead of him, the machine gobbles up all the plants in its path, before spitting out weeds, stalks and roots out of the back onto the field.

Meanwhile, two workers are busy separating out the damaged tomatoes, stones and chunks of earth from the pile. The healthy tomatoes are rolled over a conveyor belt and into a trailer driving alongside the harvester. But how do the tomatoes survive the whole operation unscathed? “These tomatoes are not like the typical salad tomatoes available on the market,” explains Santa Vittoria, a strongly built farmer with a beard to match. “For our tinned tomatoes, we grow robust varieties with thick skin and low, bushy plants.”

A man committed to quality: Marco Franzoni is constantly working to improve his tomatoes.

Summer in northern Italy is tomato season. Truckloads filled with tonnes of the plump fruits exuding the scent of ‘Passata di Pomodoro’ are transported from Italy’s ‘Food Valley’ to large factories in the surrounding area every summer. Here the tomatoes are boiled down, at times concentrated, and tinned by the millions. The area around the city of Parma is better known for its ham and hard cheese. Parma ham and Parmesan cheese both bear the name of the picturesque university city set on the banks of the Parma river. But tinned tomatoes? Although it’s a given that no bolognese or salsa is complete without them, until recently hardly anyone had paid much attention to the cheap product and where it came from.

Quality and sustainability produce a market leader

Tinned tomatoes from Italy haven’t always got the best reputation, especially due to concerns that tomatoes and puree used in products were actually being sourced from China and labelled as being “Made in Italy”. Now consumer rights activists, chefs and TV show panellists are taking to tasting and rating a whole host of different tinned tomato brands. The frequent winner: Mutti from the Italian province of Parma. Mutti has worked its way up to the top of Italian food market thanks to the quality and sustainability of its tomatoes, and despite its produce costing quite a bit more than its competitors. Mutti’s products have now firmly cemented their place on supermarket shelves across a total of 95 countries.

Tradition meets modernity. Francesco Mutti has tirelessly striven to take the family business forward.

Around 850 farmers grow produce for Mutti in and around the area surrounding its main factory in Parma. One of them is Mr Franzoni. He sets aside one seventh of his 350ha of farmland to tomato cultivation. The rest is used to grow wheat or grass for his cows to graze. When he started out, Mr Franzoni also supplied other companies. Now he works exclusively for Mutti. “They place a great emphasis on quality, I like that,” he grins. “They take pride in their work.”

Fair prices for farmers

Mutti not only pays its farmers 10% above the seasonally fixed average price, but it also awards annual prizes to suppliers who deliver the best quality produce. In the north of the country, that adds up to some 40 farms every year. At the end of the harvesting season, the best of the farmers chosen receives a gold medal and an additional cash bonus.

Mr Franzoni has already been crowned the winner of this prestigious award, worth several thousand euros, no less than five times. “I have mostly invested the money I have won in equipment.” If he wins again this year, Mr Franzoni wants to buy a GPS system for his planter so that he can work with even greater precision and conserve more resources.

I have won the quality award for my tomatoes five times. I mostly invest the bonus money in new equipment.

Marco Franzoni, Farmer

The dark side of the tinned tomato business

It was and remains the farmers and harvesters who bear the brunt of dumping prices for tinned tomatoes. In the north of Italy, sowing, care and harvesting are all done by machines, apart from the few workers employed to sort through the crop collected by harvesters. In the south, it’s a different story. There, tomatoes are still harvested by hand, often by underpaid undocumented migrants. Recently, the death of a Malian harvest worker while at work in the field due to excessive heat in Apulia caused outrage across the country.

Until six years ago, Mutti had an agreement with its 200 contract farmers in the South of the country to ensure fair wages, sufficient breaks and an insurance program for the harvest workers. “But we found that it was not possible to reliably monitor these conditions were met,” says Ugo Peruch, the company’s agricultural director. Since then, Mutti has only worked with farms that produce by machine, even in the South.

Research and digitalisation for the future

In addition to paying its farmers fairly, Mutti supports them further by investing in research, training and a digital learning platform. The company’s efforts are primarily focused on saving resources, in particular water. The introduction of drip irrigation, the optimisation of irrigation times and cycles, and equipping farmers with special measuring devices to record data on their crop’s microclimate have enabled water savings of up to 30%.

A familiar scene in Italy’s Food Valley: Hangers fully loaded with tomatoes.

In addition, pesticides have been reduced by 10%. “We want to considerably reduce our pesticide use even further,” explains Mr Peruch. Good tomatoes make tasty sauces. That much is clear. But first, they have to be processed correctly.

In the factory courtyard, truckloads of tomatoes parked bumper to bumper are ready to be weighed and undergo the first quality checks. The factory processes 300 loads a day. That’s 7,500t, enough to fill 2.5 million tons of tomatoes. In just 10 weeks of harvesting, Mutti has the task of filling its thousands of square meters of warehouse space to ensure it has sufficient stock to last the year.

From turf to tin in just a few hours

The trailers of tomatoes are first rinsed with water. Down waterfalls, in slowly turning drums, through canals and under sprinkler systems: The tomatoes rush into basins the size of swimming pools. While they are rinsed, plant debris, stones and unripe or damaged produce are continually separated from the good tomatoes, both by hand and with the help of sieves and optical sensors. The healthy tomatoes are then placed in a waterbed, where they make their way inside the factory via wide transport routes. There, the washing and sorting process continues.

Hard skin, aromatic core. Only robust varieties are suitable for tinned tomatoes.

Although the tomatoes have already been sorted in the field, a fifth of the total quantity delivered to the factory goes to biogas plants or feed troughs. The remaining tomatoes proceed to the next stage of processing. In a patented process, the tomatoes are pressed at low temperatures before being turned into pulp, passata, pizza sauce or puree. Exactly how this is done remains a company secret. In any case, heat is only applied to the tomatoes at a later stage and only for some products. Less than three hours after their arrival at the factory, the tinned tomatoes and tomato puree tubes made of only the ripest tomatoes are ready for the supermarket shelves.

Inside Francesco Mutti’s office

“Our careful preparation of tomatoes is one of the main reasons why they taste so good,” says CEO Francesco Mutti. The 53-year-old business tycoon is sat at a glass table, behind which stacks of Mutti tins from across the ages recount the history of the family business – now in its fourth generation of family leadership. Your attention is immediately drawn to Mr Mutti’s striking grey sideburns. The top button of his shirt collar is undone, his suit jacket and tie hang on a rack in the corner. Mr Mutti’s style is casual and dynamic. He can initiate change and inspire other people to try out something new.

Bringing the factory to the field

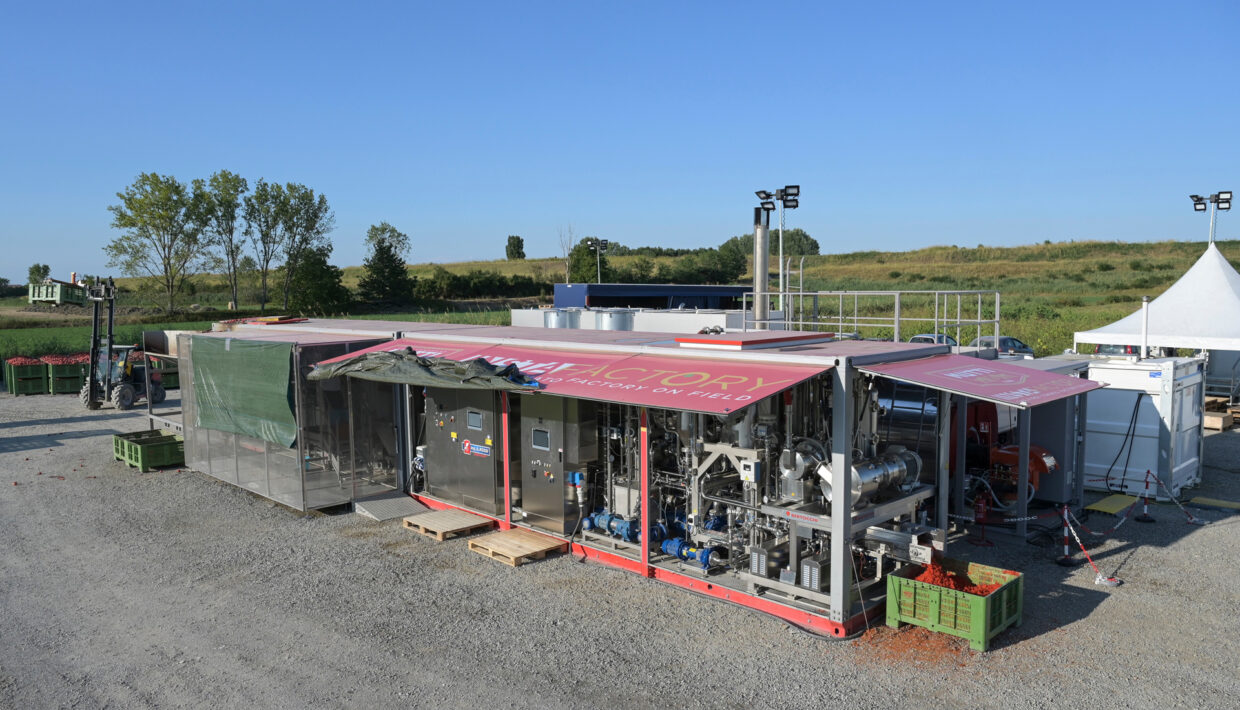

For a prime example of Mr Mutti’s ability to initiate change you needn’t look any further than his so-called InstantFactory. This novel concept is located on a gravel car park, only a few hundred meters from Mr Franzoni’s tomato field. The small mobile factory of containers steams and hisses away as it gets to work.

Nicolas Jacoboni is the chief engineer in charge of getting the new plant up and running. In his safety shoes, he hurries back and forth between feed chute, tanks and steam generator, tightens hoses and checks pressure gauges. He stops for a moment in front of a control glass. At this point, all that can be seen is hot water running through for sterilisation purposes. A short time later, deep red passata is shooting through. One last look at the circuits and temperature indicators on the display, before Mr Jacoboni nods with satisfaction. “Once the system is up and running, it does all the work by itself.”

It doesn’t get any fresher than this. Even the more delicate tomato varieties can be processed in this way. And the process also saves on transport. But above all, the passata is produced in small quantities that can be assigned to individual farms, in accordance with the nature of their soils and the respective microclimate, similar to a Terroir wine. The quantities of tomato passata produced are correspondingly small, at least by Mutti’s standards. One million bottles of the so-called Passata sul Campo will appear on the Italian market this year. In Germany, the number is just 25,000.

In the evening, the InstantFactory continues its work under floodlights. While Mr Franzoni has long finished for the day and lies in bed, there is no respite for the machines. The remaining tomatoes that weren’t turned to passata during the day are packed in large boxes at the edge of the gravel car park. Forklifts drive back and forth, emptying them into the InstantFactory’s feed chute. Mr Franzoni will be back in the morning and set to work once again, driving his harvesting machine through his field full of ripe tomatoes.