Interest in the soil often stops at the top 30cm – where ploughing, sowing, and sometimes harvesting take place. But below this lies an area that is equally important for plants: The subsoil. It contains large reserves of water, nutrients, and organic matter.

In dry years, it can be crucial for plant survival, provided the roots can reach it. However, compacted layers – caused by the use of heavy machinery, among other things – frequently prevent this from happening. Consequently, the root system remains shallow, and the plant only utilises some of the available water.

Topsoil and subsoil – two worlds beneath the field

Topsoil (0–30cm) is quite homogeneous, nutrient-rich, and generally allows for good root penetration. Here, the farmer focuses on soil structure as well as air and water balance, ensuring optimal conditions for plant growth.

Below this lies the subsoil, which can extend several metres down to the parent rock. It stores about half of the water available to plants, contains 20–30% of the nitrogen and phosphorus reserves, and an average of around 40% of the organic carbon. The problem is that around 70% of German arable soils have root-inhibiting layers, meaning that plants often cannot utilise this dormant underground reserve.

When the subsoil can be penetrated

Prof. Dr. Axel Don

by roots, plants are able to cope far

better with periods of drought.

Farmers can use certain measures to influence the structure of the subsoil with the aim of increasing yields. These measures are known as subsoil melioration. “If the subsoil is penetrable by roots, the plant can endure a dry phase much better,” emphasises Prof Dr Axel Don from the Thünen Institute of Climate-Smart Agriculture. Measurements show that improved sites experience significantly reduced yield losses during drought years.

“In normal times, it might be enough just to have the topsoil. But in extremely dry conditions, the plant can no longer manage with the water in the topsoil. Then it needs the subsoil,” explains the soil scientist. A loose subsoil also offers advantages during heavy rain. A loosened structure improves the aeration of the subsoil and its water absorption capacity, providing good protection against water erosion.

Subsoil in figures

10-80%

of their water and nutrient needs meet crops from the subsoil – if they can.

approx. 50%

of the water available to plants is stored in the subsoil.

20-30%

of the nitrogen and phosphorus reserves are located in the subsoil.

20%

of the humus build-up occurs in the subsoil.

70 %

of German arable soil is affected by root-inhibiting compaction.

Paths into the depths – how plants can reach the subsoil again

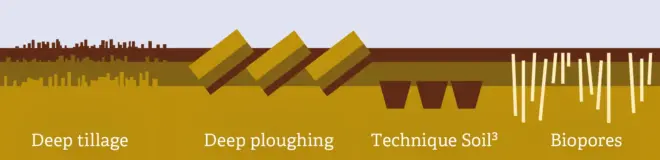

There are various approaches to breaking up compaction in the subsoil. These include mechanical deep tillage methods as well as biological measures.

Deep tillage

Implements like subsoilers or deep rippers perform deep tillage to a depth of around 60cm. This practice is used on approximately 6–7% of arable land in Germany. However, the effect usually only lasts for a short time if no subsequent stabilising measures are taken, such as sowing deep-rooting crops like lucerne.

Deep ploughing

Deep ploughing involves inverting the topsoil and subsoil, allowing humus-rich topsoil to reach deeper layers. This method is only suitable for light sandy soils, as it impacts soil structure. “If you use the wrong technique at the wrong time, you can destroy more than you gain,” warns Prof Don.

Biological tillage through taproots

Taproot plants like lucerne or chicory create permanent biopores – metre-deep cavities that can last for decades. Subsequent crops utilise these natural root channels. Tests show that in dry years, biopores increase grain crop and rapeseed yields by up to 30%. The drier the year, the more pronounced the advantage.

The Soil³ project – compost as a structure stabiliser

As part of the ‘Soil as a sustainable resource for the bioeconomy’ (BonaRes) programme, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), the Soil³ project (2015–2025) aimed to make deeper soil layers usable as a resource. The researchers developed a technique for subsoil melioration that is gentler than deep ploughing and has a longer-lasting effect than deep tillage.

The result isthe so-called Soil³ technique: First, the topsoil is pushed aside with a ploughshare on 30cm wide strips. A deep spader then loosens the subsoil and mixes in compost to a depth of 50–60cm. This both loosens and stabilises the soil, leading to measurable long-term effects, as shown by field trial results.

- + 20–25% higher grain yields compared to the control

- + 50% higher maize yield in the first, very dry year

- Effect unchanged even after eight years

- Amortisation after three to five years (at €700 – 800/ha / £608 – 695, plus costs for compost)

The measure is particularly advantageous where soil was previously compacted. Sandy soils benefited more than loess soils. No increase in nitrate leaching from the subsoil was observed – on the contrary, plants were able to make better use of water and nutrients.

The method is not yet ready for practical use. Sufficient quantities of compost are not yet available for large-scale applications, and the specialised technology is also not yet accessible. Additionally, there are uncertainties in terms of legal categorisation. According to the German Federal Soil Protection Act (BBodSchV), the introduction of organic materials into the subsoil is currently prohibited. Whether compost falls under this or is covered by the Fertiliser Ordinance in this process remains uncertain.

Alternative: Partial deep tillage

An option without compost is partial deep tillage, where the soil is ploughed in strips to a depth of 60cm. This allows topsoil material to enter the subsoil. The same applies here: Caution is advised with clay soils, as the soil structure can be easily damaged. A suitable plough is expected to be introduced to the market in the coming years.

Lilian Guzmán from the Gross Machnow agricultural co-operative is testing the method on the sandy soils of Brandenburg – with an average of 28 ground control points. “We are hoping for an increase in yield,” explains the farmer. And in the first year, 2024, the green-cut rye on the deep-tilled strips yielded 9% more than the variant with the conventional plough and 44% more compared to the field cultivator. Grain maize, on the other hand, did equally well in all variants in the wet year of 2025. “The year wasn’t bad enough,” concludes Ms Guzmán.

In addition to mechanical methods, the Thünen team is investigating artificially created earthworm channels. To achieve this, fine holes (8mm across, 80cm deep) are made in the ground. Just three months later, 90% of the pores were occupied by roots, which resulted in 2–15% higher yields. Earthworms also quickly colonised the tunnels. “They are like motorways for the roots in the subsoil,” says Prof Don enthusiastically. “That could be the solution. The system returns to a natural state, so to speak.” Questions about the optimum number of holes, depth and stability are still unanswered.

Looking into the depths is worthwhile

While the Soil³ technique, deep ploughing, deep tillage, and crumb deepening are particularly beneficial for sandy soils in north-eastern Germany, creating biopores is more suitable for clay soils. All these methods are costly and energy-intensive. General recommendations are difficult because of the significant natural variability of the subsoil, even within a single field.

Determining the best measure and its expected impact is therefore always a site-specific and farm-specific question. The benefits and risks of such an intervention in the soil should be carefully considered. Technical, economic, and – in some cases – legal hurdles still remain. Those who dig deeper – both literally and figuratively – and focus on their subsoil, lay the foundation for stable yields under increasingly extreme weather conditions.

The Soil³-Projekt Participants

- Rhenish Friedrich Wilhelm University of Bonn

- Technical University of Munich

- Forschungszentrum Jülich

- Free University of Berlin

- Johann Heinrich von Thünen Institute

- Ecologic Institute

- Humboldt University of Berlin

- Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF)

- University of Kassel