Mr Berges, the NIR sensor tells us exactly which nutrients the slurry contains. Does this mean that, in practice, the fertilising strategy also changes?

Yes, absolutely. Obviously nature is hard to predict – the weather doesn’t always stay the same and neither does the slurry. The NIR sensor enables farmers and contractors to determine the three important nutrient levels in the slurry continuously and in real time. This brings a certain level of transparency to nature’s unpredictability and has very positive effects. I would even go so far as to say: This is a breakthrough for fertiliser strategies.

Alexander Berges is manager of production systems for dairy and livestock farming at John Deere.

What exactly does that mean for different operations?

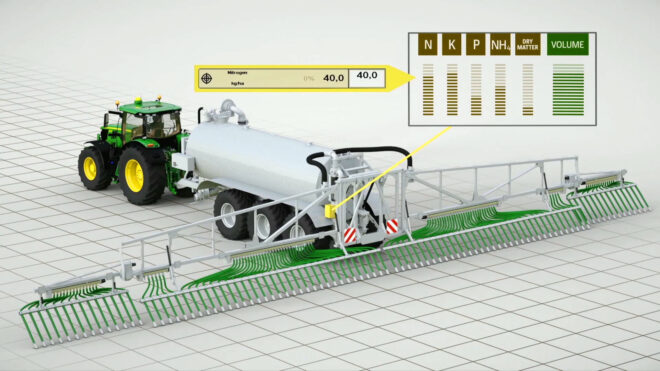

Let’s take a look at two typical kinds of operation: First, we have livestock farming. Slurry has been used as a fertiliser in this field for decades. So it’s nothing new for these farmers. But now with the NIR sensor, they know exactly how they can take advantage of it. So we no longer refer to cubic metres of slurry per hectare, but kilograms of nutrients per hectare. This means we can avoid over-fertilising livestock-dense areas, and prevent the well-known side effects on the soil, water and air.

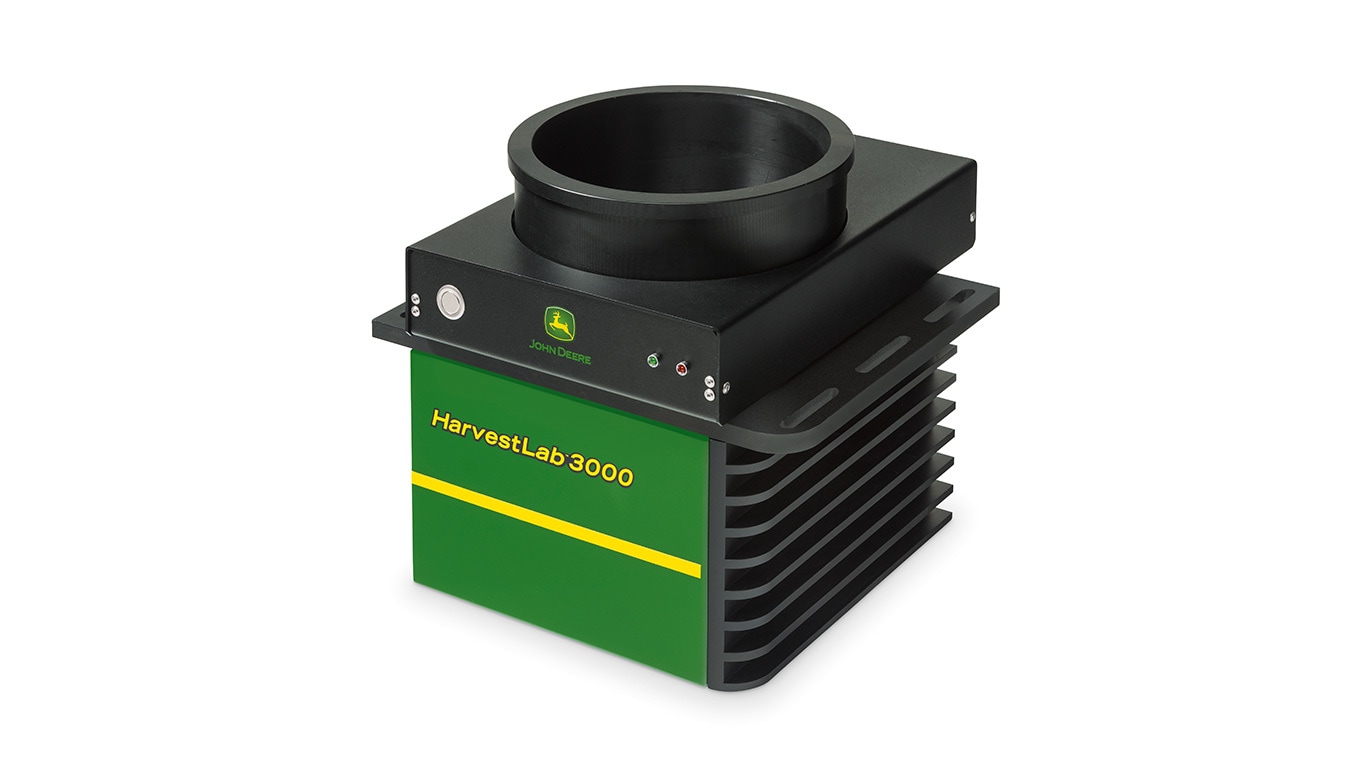

HarvestLab 3000

Near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy to analyze various constituents within harvested crops, silage or slurry (one sensor, three applications)

And the second example would be arable farming. In the past, a lot of arable farmers had their reservations about using slurry. They’ve been using mineral fertiliser for decades, and they’ve had a lot of success with it. But at the same time, this interrupted a natural nutrient cycle which had formed over millennia. NIR technology has now brought arable farmers’ attention back to the option of using slurry. These farmers are used to measuring their fertiliser in kilogram per hectare. By using the sensor, they can now do exactly the same with slurry.

To put it simply: Can slurry 100% replace mineral-based fertiliser?

If you drop the number 100, then I could answer that question with a yes. We can and we should substitute mineral-based fertiliser with slurry, but not entirely. Taking organic fertilisers as an example – whether they are in solid form as dung or liquid form as slurry – then we generally have phosphate as a limiting factor.

We can now substitute mineral fertilisers with organic ones in order to achieve the optimal P value for whichever crop we are working with. However, there are still gaps in the potash and nitrate values – mineral fertiliser can be used here. So the rule of thumb is: As much slurry as possible and as little mineral fertiliser as necessary. But it remains clear: We can’t completely do away with mineral fertiliser yet.

The HarvestLab sensor allows us to accurately spread slurry, measuring the nutrient content in kg per hectare and helping to substitute mineral fertilisers in arable farming, too.

What are the other advantages that slurry brings us?

First of all, using slurry is advantageous because – as I said before – we can close nutrient cycles. With slurry we can also achieve better soil fertility and an improved humus balance. And it’s this last advantage which is going to play a huge role in the future because arable farming can be a drain on carbon. Using slurry makes it 10 times easier to maintain or raise the humus level and in doing so, slowly draw CO2 from the atmosphere. And last but not least: Using slurry also saves us diesel.

You’ll have to help me out on that one.

Of course, it’s one of my favourite topics, since not many people know about the concept. Focusing on the way we use agricultural machinery over the farming season, we can see that these machines use diesel. Adding up this consumption gives us a total of between 60 and 100 litres of diesel per hectare per year, depending on region, soil type, and cultivation method.

But if we take arable farming as an example, which uses mineral-based fertilisers with 160kg nitrogen, then around 160 litres of diesel are also required to produce that 160kg of nitrogen. This is made artificially, which is why it is often called artificial fertiliser. Assuming that, using NIR technology, arable farmers can substitute half of the mineral fertiliser with slurry, then it is clear: Each farmer saves exactly 80 litres of diesel per hectare over 365 days. This is a huge step for sustainability.