Olaf Stammer still remembers a time just 10 years ago when a farmer would be proud to sell for 15 cents more than his neighbour. “After the 2007-2008 season and the onset of major price increases, it took me some time to adapt,” admits the farmer from Bad Schwartau in Northern Germany. “And I am still learning something new every day.” In order to simplify input purchasing and streamline the process for trading and selling its products, this family farm teamed up with three neighbouring grain producers to form a joint-stock company. Together, their operation covers 720ha, with storage capacity for 5,000t of grain and Mr Stammer managing sales operations.

412m t

Total volume of grain traded globally in 2017/18 (FAO forecast, April 2019)

Adapting to atypical years

Today, Mr Stammer uses a security strategy, while also maintaining a system to enhance sales performance. “When I first started trading, I was moving big batches – as time went on, I started to break things up as much as possible. Since then, I’ve sometimes sold stock in tenths or twelfths. This allows me to feel more secure and to stay on top of the market,” he explains. “In contrast, if I were to sell the harvest in quarters, and then the market rebounded just after the deal, that could mean in retrospect I would have made a poor sale.”

Olaf Stammer

The farm company works with several merchants: Contracts are drawn up in the spring, but most of the grain goes out at a fixed price between December and the following harvest. “What makes it difficult is that there will always be new situations and atypical years, so it’s important to be able to react and adapt.” Mr Stammer also emphasises how important it is for farmers to familiarise themselves with the futures market. This makes marketing and selling the grain much more complex – but also better-informed. Although in the not-too-distant past the farmer’s job was simply to: “Look after his fields and his livestock,” today the job requires an awareness of global affairs going well beyond the immediate professional environment.

There will always be new situations and atypical years.

Olaf Stammer

In addition to information about global stocks, the state of crop production, exchange rates and input costs, Mr Stammer also considers it necessary to keep an eye on political developments, as protectionist leanings halfway around the world can have a short-term effect – positive or negative – on the Matif commodity futures exchange in Paris.

Zero speculation

About 200km to the east, Roland Marsch trades crops grown by his two sons, one in Jarmen in the German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern with 1450ha (cereals, rapeseed and sugar beet), and the other in Estonia with 1,400ha. “It’s always difficult to forecast how markets are going to develop,” says the farmer, who worked in the grain trade for six years. “My rule of thumb is: When prices are relatively good in comparison with previous years, you have to sell, without hesitation and in small quantities. Trying to get the best possible price for 100% of your crop would be dangerously speculative.”

Roland Marsch

He cites the 2015-16 season, during which an expected price rise failed to materialise, and he was forced to sell a large portion of his harvest during a downturn, with the market occasionally bouncing back via a few very short-lived bright spells. Taking such a strategy in an overall bear market allowed him to get the most out of a tricky situation: “Successful trading is also about courage; taking action even when prices don’t seem that attractive.”

Trying to get the best possible price for 100% of your produce would be dangerously speculative.

Roland Marsch

In order to remain profitable, every strategy must take into account the internal organisation of the farming operation, warns Mr Marsch. “We have a lot of contracts, but we also make an effort to have only one buyer per crop so as to streamline delivery costs as much as possible. Resources, both human and material, must be put to the best possible use as part of an overall sales strategy,” he explains. “And of course, working with greater quantities allows us to better manage quality parameters via scaling measurements.”

Clear objectives and strategy for marketing

Patrick Bodié, head of “Mes Marchés” (My Markets) at the Chamber of Agriculture in Aube, France, says it is important for each farmer to find the approach that works for him. For example, even though average prices may turn out to be lower than fixed prices, they may still be preferable when the farmer is having difficulty in making selling decisions. “In such cases, farmers are better off delegating sales operations to their grain storage co-operative.”

128 €/t

Volatility of wheat price traded at the French seaport of Rouen between 2013 and 2017

In a more general sense, Mr Bodié also recommends limiting the amount of time spent gathering information, and instead keeping an eye on the big picture. “Too much constantly- changing information can stifle our ability to take action. Successful sales are not all about industry expertise, as some people mistakenly think. Of course, you do need to know the market and the commercial tools involved, but the most important thing is to define a strategy and set objectives.” It’s essential to establish a spreadsheet of key values, including the profit threshold, based on fixed costs and expected revenues, as well as the farm’s historical buy/sell prices. Based on the objectives in question (such as security or optimisation), the strategy will then set the next steps for upcoming seasons. “You have to be able to look down the road, and set yourself a pricing perspective over the next two years.”

Knowing the figures

Maintaining a simple and efficient approach to tackle the complexity of market mechanisms is the tactic favoured by Éric Collot. He heads a 112ha arable operation near Prunay- Belleville (Aube), including wheat, spring barley, sugar beet, alfalfa, rapeseed, and pharmaceutical plants. “The hardest thing about grain trading is knowing when to pull the trigger,” he says. “You can’t let yourself be taken in by the prices. I use the average price of my sales from the last three years as a basis, and I sell everything that falls above that. I start from the idea that the costs from the last three years are relatively consistent with my structural costs, and I know what level of profitability I’ve had at those prices.”

Éric Collot

With wheat yields highly stable, Mr Collot (who stores most of his own grain) only sells at fixed prices. Having invested in the markets for the past 14 years, he retains futures trading options to benefit from price rises, but rarely goes through partners for this, instead preferring to maintain his own futures market account.

You can’t let yourself be taken in by the prices.

Éric Collot

“In 2016, I had pre-sold 60% of my wheat before harvest, because I noticed significant economic patterns that pointed to a price drop,” he explains. “Due to very poor weather, that 60% ended up representing almost the entire harvest.” Mr Collot’s intuition allowed him to come out of this difficult season in the black, with an average reduced net price of €170/t. Despite the loss of income due to lower wheat yields, the farm was able to secure a modest profit in the 2016-2017 season thanks to the price achieved and the diversification of production. “Weather patterns in recent years have made it harder for us to control the quantities, protein levels, and specific weights. We must therefore try to stay on top of as many aspects as we can in order to secure our revenue streams: Firstly in terms of prices, and also via very careful management of all the other economic factors.”

Risk and opportunity

Although futures markets will always carry a certain level of unpredictability, they do offer greater transparency and thereby potentially fairer prices, insists Mr Bodié. He contends that farmers now understand this, noting that demand for training in these subjects is growing. A survey carried out by the Aube Chamber of Agriculture between 2010 and 2016 showed that grain prices were the top factor in determining profit margins, ahead of cost optimisation and yield. Still, the commercial environment has changed considerably over the past few years, and those who fully understand the market and are actively involved in trading will be best placed to capitalise on this.

270,5m t

Estimated total global wheat stocks for 2018/19

At the same time, we are also seeing a boom in decision-making tools. There are now a wide number of options not only for securing revenues in a difficult climate, but also allowing users to save or invest. “It’s also possible to see a silver lining in increased price changes,” hints Mr Bodié. “On the one hand it’s seen as risky, but it can also be viewed as an opportunity.”

Price is not only determined by weather any more

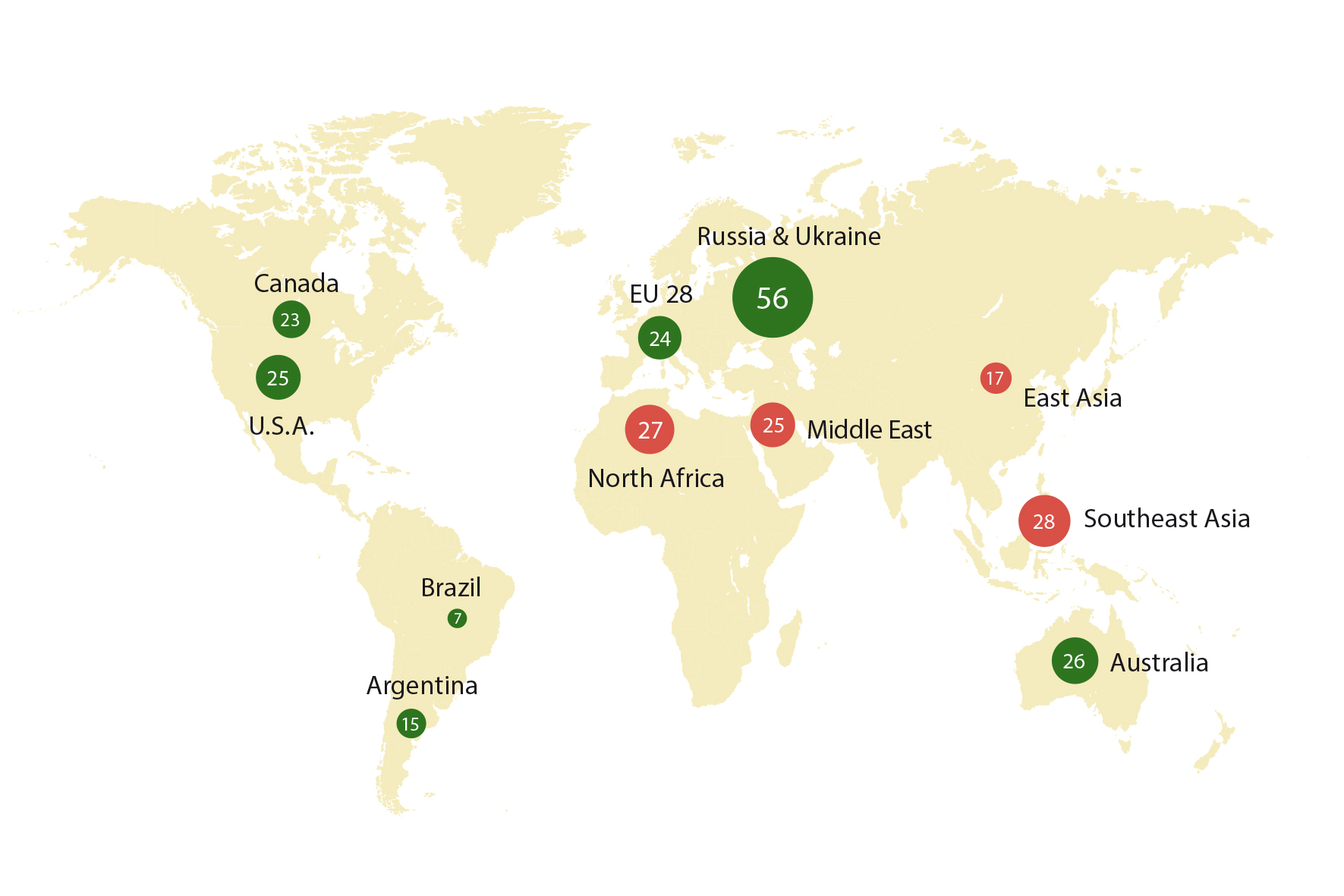

Global imports and exports of wheat 2017/18, mill. t.| Green: exporting countries/regions; Red: importing countries/regions

What does the international grain market look like right now, and what developments are to be expected in future? “Russia, the Ukraine and eastern European countries have become much more dominant in the supply of grain to the global market,” says Jack Watts, lead analyst at AHDB – the UK’s grain levy board. At the same time, rising investment and the adoption of GM crops have propelled Latin America onto the scene.

Although the US and Europe remain the top-flight producers, the environment is becoming more and more competitive. “We are more reliant than ever on emerging economies, which creates a lot more uncertainty as these have less transparent markets with more erratic weather, currency and politics.”While global supply is still sourced from a handful of major exporters, import demand is becoming much more diversified. The key markets are in north Africa, while the Middle East and Saudi Arabia are emerging importers; the Saudis in particular are looking to increase imports to preserve their water resources, explains Mr Watts. Asian demand is also increasing, linked to its growing middle classes and westernisation of diets.

Rising wheat demand in Asia

Chinese demand for fodder crops has soared in recent years, but the rest of the world’s ability to increase production to meet this demand has been under-estimated, he adds. Chinese policy also led to a rapid increase in self-sufficiency; so much so that policy then changed again to run down the large maize stocks. “China reportedly holds 40-50% of the world’s wheat stocks, but nobody really knows.” Chinese demand will certainly continue to increase, but it will be difficult to forecast by how much, given the lack of government transparency.

In terms of production, Russia and Brazil remain the ones to watch. “Production has increased significantly but the infrastructure for exports has not kept up, creating a number of bottlenecks and disrupting grain flow,” says Mr Watts. With the world now in a period of relatively low grain prices, investment to improve that infrastructure is unlikely to be forthcoming.