There’s a peaceful tranquility to the endless rolling landscape of the Flint Hills that’s a little misleading. Take a springtime drive down the interstate highway that slices through this eastern Kansas grassland and you’ll see scattered groups of stocker cattle (animals weighing 180 to 270kg) grazing lazily in lush green pastures. However, go behind the scenes, on the narrow blacktops and dusty rock roads that serve North America’s last stretch of tallgrass prairie, and you’ll witness the turmoil of turnout in the Flint Hills.

Turnout is how locals refer to the 20-day period in the spring when cattle from more than 1,000 miles (1,600km) away flood into the Flint Hills to graze on the rich, early growth of the native grass. Thousands of semi-trucks, each hauling 100 cattle or more, growl over the hills and through the scattered cow towns around the clock to deliver nearly a million head to their summer-grazing home.

Timing is critical

“Turnout gets a little crazy,” said Pat Swift, manager of Livestock Dispatch in Cottonwood Falls, Kansas. “I load about 75 trucks a day, and there are three or four other guys in town doing just as many. On bigger pastures, some that are up to 4,500 acres (roughly 2000ha) in size, there can be 25 to 30 trucks lined up waiting to unload cattle.”

Mike Holder, district Extension agent for Chase County, Kansas, puts this annual undertaking in perspective. “There are 2,900 people who live in this county, and farmers and ranchers here raise about 2,000 cows through the year. But over about 20 days, usually starting in late April, more than 1,000 trucks bring in 120,000 stocker cattle, and we’re only 10% of the Flint Hills,” he says of the numbers.

“Timing is critical,” said Cliff Cole, manager of the Ranch Management Group that oversees seven Flint Hills ranches with an inventory of more than 50,000 cattle. “We need to get as much weight on our cattle as possible, and that means getting pastures stocked on time. It’s like harvesting wheat or planting corn – every day is extremely valuable.”

“The cattle come from everywhere,” added Swift. “Many are right out of Mexico, others come from grazing on winter wheat fields in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. Some cattle come from the Corn Belt, where they grazed on corn stalks, and others out of Tennessee, Alabama, and the southeast. It takes every livestock hauler we can find to get the job done.”

Cheap gains

Trucks haul cattle to the Flint Hills today for the same reason train cars and trail drives have brought them over the past 150 years. It’s unquestionably the most efficient and economical place in the world to add weight to cattle. In the early spring, the native bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) pasture is so high in protein and minerals that the daily rate of gain on yearling steers rivals that of feeding corn, but at a significantly lower cost and with much less labour. “It’s truly amazing grass,” says Taylor Grace, a fourth- generation Missouri rancher whose family has pastured cattle in the Flint Hills for nearly three decades. “In central Missouri, our cattle gain 1 to 1½ pounds a day (0.5 to 0.8kg/day), but send them to the Flint Hills from April to September and they gain 2½ to 4 pounds a day (1.2 to 2kg/day).”

In central Missouri, our cattle gain 1 to 1½ pounds a day (0.5 to 0.8kg/day), but send them to the Flint Hills from April to September and they gain 2½ to 4 pounds a day (1.2 to 2kg/day).

Taylor Grace

At the Henderson Ranch, near Warsaw, Missouri, Grace helps growing cattle gathered from local cow/calf producers. “In April, we send several thousand head to graze on pastures we rent in the Flint Hills, either in doublestock or full-season programs. Pasture rent is heavily influenced by the price of corn, and ranges from $70 to $130 (€60 to €115) per animal,” he said.

Increasing stocking rates

Three decades ago, range management specialists at Kansas State University developed an intensive early stocking program that transformed both the calendar and the cash flow on many Flint Hills ranches. The traditional season-long program has cattle on the grass for 150 days at a stocking rate around four acres (1.6ha) per animal. In contrast, intensive early stocking takes advantage of the fact that the greatest gain is in the first part of the season. After mid-July the grass quality declines as nutrients are transferred to the roots.

Holder explained that by doubling and even tripling the traditional stocking rates, cattle are ready to move to feedlots, typically located in western Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Texas, after grazing just 90 days. Research studies found the more intensive approach resulted in the production of an additional 35 pounds of beef per acre (40kg/ha).

“So many ranches have shifted to intensive early grazing that the bedlam has gotten nearly as bad when cattle come off the grass in July as when they go on it in April. And, since they weigh 200 to 300 pounds (90 to 140kg) more than when they came, it actually takes even more trucks to haul them out,” said Holder.

Boost from burning

Volunteers like Bobby Godfrey help explain the tallgrass culture to visitors at a recent Symphony in the Flint Hills.

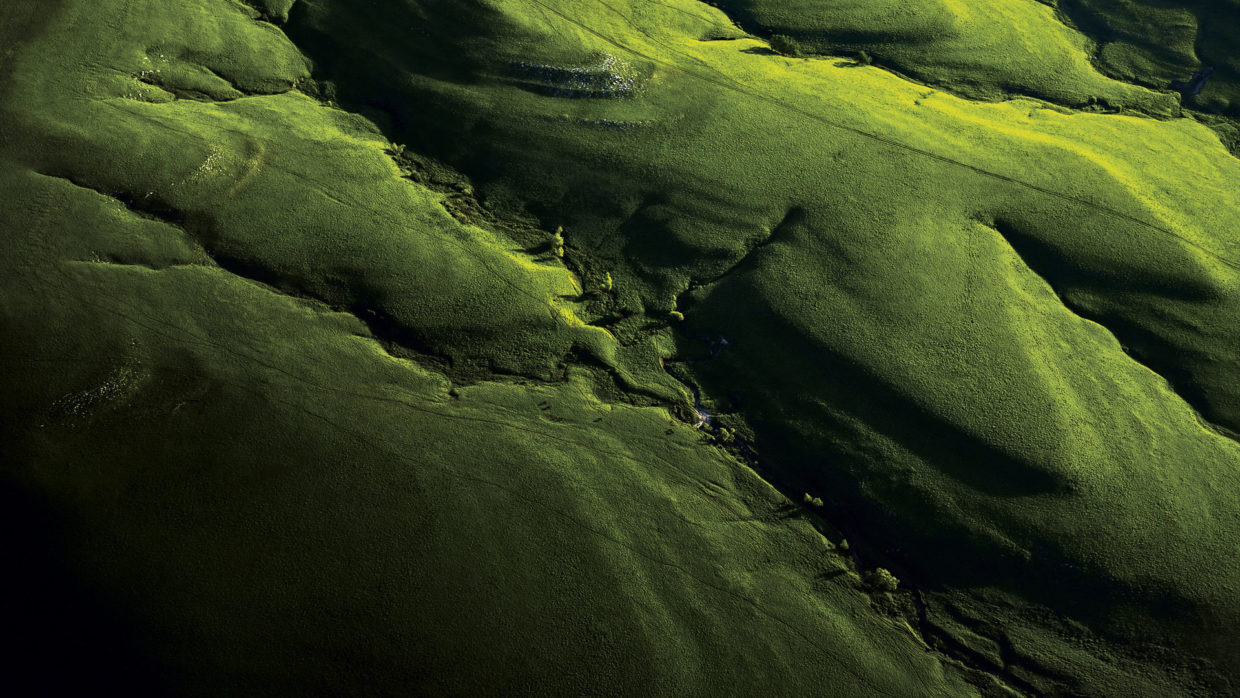

Three features are largely responsible for the beauty and the bounty of the Flint Hills: shallow topsoil, fire, and a grazing culture. The first of those, the imbedded layers of shale and limestone that the first homesteaders encountered, spared 4.5m ac (1.8m ha) of the grassland from their ploughs, the fate that befell the rest of the original 150m ac (60m ha) of tallgrass prairie.

Fire has long been a critical part of the Flint Hills’ ecosystem. Regular burning, whether due to lightning, native American Indians, or today’s ranch managers, has been a proven way to boost productivity and also ward off the weeds and woody species that would otherwise turn the prairie into a woodland.

“Mother Nature used fire to take care of the grass hundreds of years before cattle got to the Flint Hills, and we’ve learned to do the same,” said Ryan Arndt, a third-generation rancher from Emporia, Kansas. Kansas State’s Clenton Owensby says steers grazing on pastures burned at the beginning of spring growth of the dominant tallgrass species will gain 32 pounds (14.5kg) more than on an unburned pasture. “Fire removes the old dead grass, allowing the soil to warm which spurs soil microbial activity and nutrient uptake. Also, burning releases nutrients in the old material and destroys woody growth,” he said.

Smoke as part of life

Prescribed spring burning and proper grazing are critical to management of the tallgrass prairie.

Fire also creates smoke, and excessive amounts of it have raised air quality concerns in communities downwind from the Flint Hills. Two years ago, the ranching community worked with the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and state health officials to develop a voluntary Smoke Management Plan in response to those concerns. “The plan has helped some,” said Holder, “but when we burn a lot, like it looks like we will this spring, I’m afraid we could still have problems. Ranchers, and those outside the industry who have studied the tallgrass ecosystem, understand that fire is a natural evil, and a little smoke is part of life out here.”

In 1867 a steer was worth about $2 in Texas, but $40 if it could be delivered to Chicago. This huge profit potential spurred the legendary cattle drives to the Flint Hills, where cattle were fattened before being shipped east. “Large tracts of land, unbroken by roads and other development, make seasonal grazing efficient,” said Holder. “There’s a desire among many families to keep ranches together through generations. There’s also tremendous interest for current ranches to grow and for outside investors to put new ones together.”

There’s also tremendous interest in telling the story of the Flint Hills. Each spring, ranchers take turns hosting a grass-roots performance by the Kansas City Symphony. This Symphony in the Flint Hills gives local volunteers a chance to share the beauty and explain the challenges of their ranching lifestyle with a crowd largely from nearby cities of Wichita and Kansas City.

In similar fashion, the recently opened Flint Hills Discovery Center, in Manhattan, Kansas, uses an elaborate array of exhibits and programs to aid visitors in understanding the ecosystem of the tallgrass prairie. “The Flint Hills are truly unique,” says Arndt. “I feel it when riding home by the light of the moon after moving a string of cattle to a new pasture.”