A severe draught in 2018, which shot feed concentrate prices sky-high, made John and Nina Andersson reassess their beef production. Farming at Renardsfält on the Swedish west coast, they had already switched from feeding up calves for other farmers to finish, to raising steers all the way to slaughter.

But they wanted to stay in farming and keep raising cattle, so with an almost scientific approach they researched areas and niches where they would have a chance to become profitable. They wanted to achieve a sustainable income for them and their three children on the farm which John had inherited as the fourth generation, following his paternal great-grandfather.

”We came to the conclusion that if you want to be profitable you have to make more money on the meat you produce by keeping the cattle to slaughter,” says Nina. Although they were never inclined to go to large-scale production, that option wasn’t viable as farmland around their 50ha farm was never on the market, nor would it have been affordable.

Our first Wagyu calf cost us 30,000 Skr (£2275).

John Andersson

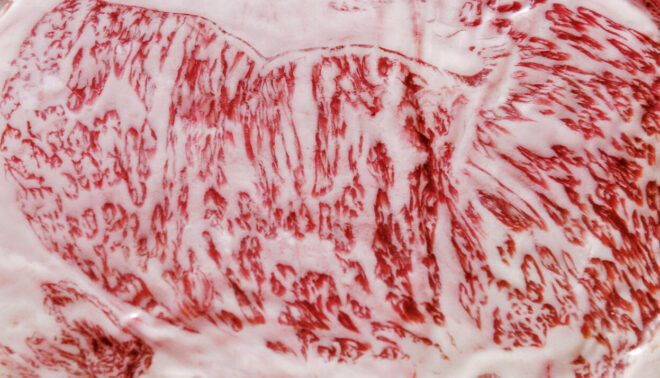

After evaluating various options and excluding niches like grass-fed or organic meat, which were already filled with existing competitors, they landed on the decision to incorporate the Red Wagyu breed – known for its high content of marbled fat and healthy fatty acids – into their herd. They bought their first embryos from Denmark in 2020. “We bought three embryos, and only one was successful, so our first Red Wagyu calf cost us nearly 30,000 Skr (£2275),” says John.

Their previous herd and Simmental legacy in Japan

Before the transition the couple had some 150 head of Holstein steers, although they were not making ends meet. Now they are aiming for half that herd, of around 75 head, as they plan on using as much home-grown feed as possible.

“We wanted to replace our previous livestock with a breed that was polled, easy to handle and with a good feed conversion ratio,” explains Nina. “That excluded some of the traditional beef cattle, so we landed on concentrating our production to a Wagyu-Angus cross, although we still have some Simmental and Belted Galloways calves.”

The couple went about identifying the best cross at an almost molecular level, befitting Nina who is a trained molecular biologist, and in-line with the scientific approach the Japanese have now adopted to enhance the Wagyu meat further. Despite their choice of the Angus breed, a Simmental cow was the first reveiver of an embryo; a breed which has traditionally been used, even by Japanese farmers, to develop the Wagyu, says Nina.

The couple settled for the Red Wagyu, which together with the Black Wagyu is the most used Wagyu breed outside Japan, of the four breeds that are classified as Wagyu in Japan. “The history of Wagyu cattle is interesting,” notes Nina. “Initially the cattle were used for pulling field cultivators and it was forbidden to eat the meat. But at the end of the 19th Century, Japan wanted to increase its meat production and crossed the Red Wagyu with Simmental to get bigger animals – and the Red Wagyu today still has some 25% Simmental genetics.”

The first Wagyu calf to be born on the Renardsfält farm was the heifer Inari, named after the Japanese goddess of agriculture, in 2021 from fertilised eggs bought in Denmark. Germany is otherwise the European country that has come furthest in developing the Wagyu breed so far.

Today, all calves born on the farm are at least 50% wagyu, and the plan is to have replaced virtually all non-wagyu animals by 2025 as they work their way up to the final count of 75 heads. The Andersson family plan to raise their cattle to slaughter at around 24 months, but will also sell live cattle and genetic material if the opportunity arises. They have already sold a bull, a 100% mix of Red and Black Wagyu for about 40,000 Skr (£3050), but Nina says the price was at the low end because the buyer had preferred a 100% Black Wagyu.

A purchase of a few pregnant Wagyu cattle in 2021 added to their still young herd and now they have 47 head of Wagyu born on their farm. “John wanted to develop our own herd by a four-breed crossing, but that would take at least four generations and the benefits of it were unclear,” says Nina.

They will increase and maintain the herd size using their own breeding stock, but eventually will have to incorporate new DNA to avoid inbreeding. They would like to buy from the US, but that road is not currently open because of bluetongue disease in the southern US means imports from that area are prohibited.

The Wagyu´s way out of Japan

Wagyu cattle have been and remain a highly cherished animal in Japan, and veiled in an almost mythical history. So there was no clear decision to share the breed and allow foreign breeders access to genetic material. Over the past 50 years access has ranged from some scientific exports and restricted exports to smuggling and outright bans, as the Japanese want to retain control over the breed.

Only four purebred Wagyu bulls were exported to the US in the 1970s for scientific research, but they were later used for breeding. Together with cunningly-used loopholes in the Japanese-US trade restrictions, some 200 Wagyu animals were then exported out of Japan. Of those, only 20 were Red Wagyu. “That is the main problem; the whole genetic pool relies of offspring from these 20 animals,” says Nina, who is focusing on raising the Red Wagyu, primarily.

Despite the industry´s own restrictive export policies, there were no formal export bans during the decades leading up to 2020, when the Japanese government suggested a full-on export ban on live Wagyu cattle and genetic material. The aim was to retain control of the increasingly popular breed and meat among western farmers and consumers.

“We´ll see what happens now because South American breeders have also started to show an increasing interest in the Wagyu,” says Nina. Today, Australia and the US are by far the biggest producers of Wagyu meat outside Japan.

The entire Red Wagyu breed relies on the genetics from just 20 cows.

Nina Andersson

Wagyu producers in Sweden

There are just a dozen or so Wagyu beef farms in Sweden and, according to the National Board of Agriculture, there were roughly 2,500 head of pure or crossbred Wagyus in the country in 2022. There is no industry organisation for breeders, who currently exchange information via social media.

The head count peaked at around 3,000 in 2017, but has again started to pick up as consumers are becoming more aware of the meat and its different taste and alleged nutritious value compared to conventional meat. It is the Wagyu’s marbled meat which is most valued.

“You can increase marbling in any cattle by feeding lots of concentrate, but that is too expensive,” says John. “But you´ll never reach the level of marbling you see in the Wagyu. To do that you need its genetics.”

Nevertheless, the Anderssons are paying a lot of attention to their feed as it also affects the flavour of the meat and they have gone about almost on a molecular level, reflecting Nina´s education as a microbiologist. Their feed formula is a fine-tuned mixture of a number of herbs and grasses such as: English and Italian ryegrass, timothy, meadow-fescue, red and white clover, alfalfa, chicory, bird’s-foot trefoil and ribwort plantain. The feed mixtures they are working with aim to enhance the already positive proprieties and healthy fatty acids in the meat, and boost its Omega 3 and Omega 9 content.

“The DNA is the most important factor for the marbling, but the feed is almost as important,” says John. Their cattle will be entirely grass-fed; they manage their pasture with a special cultivator and plan to re-seed every five year or so, with intermittent sowing of more sensitive grasses like English and Italian ryegrass which cannot survive the Nordic winters.

The Swedish Market

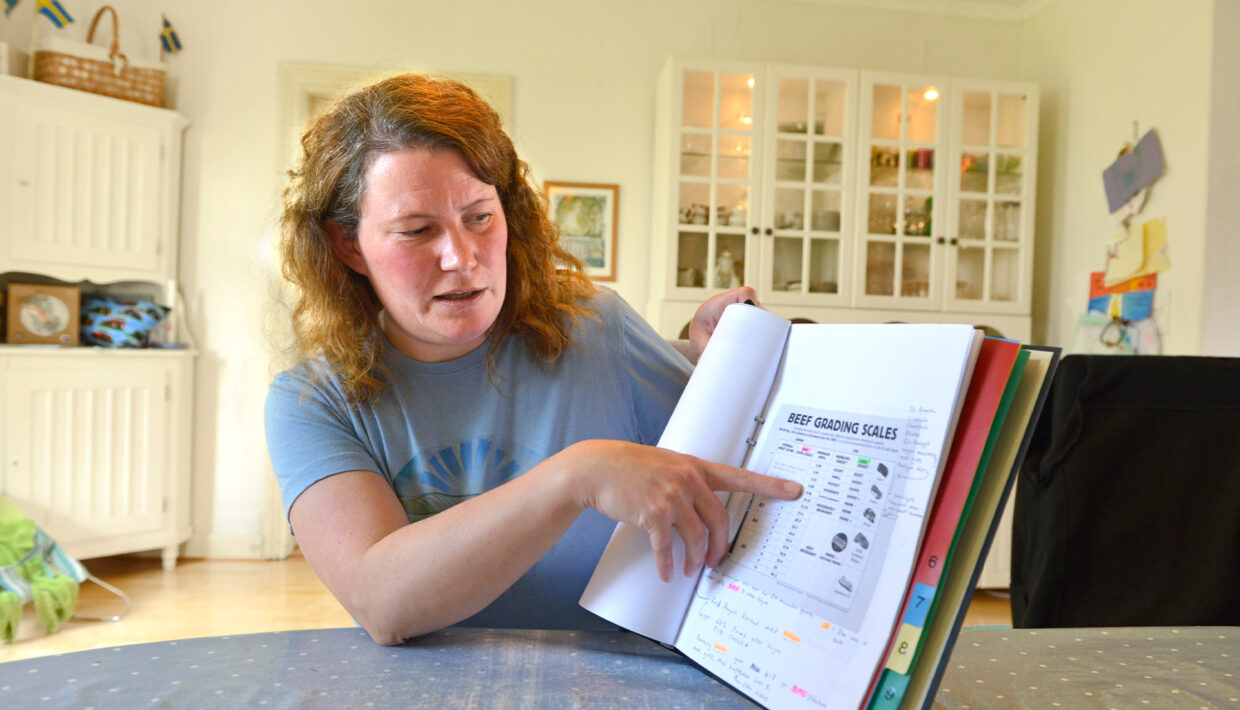

Like most other Wagyu breeders, Nina and John plan to sell their meat directly to consumers via an online shop and, eventually a farm store. Wagyu beef is not widely available in Swedish food retailers, and the number of restaurants which serve Wagyu beef is probably even fewer. Breeders are therefore facing some marketing challenges to reach consumers, who have been raised on lean meat and taught to shun fat. It’s the same in the abattoir industry, which penalises meat if the fat content is too high. “Beef at a standard supermarket reaches only 2-2.5 on the 12-grade Marble Beef Score (MBS) and only one abattoir gives you extra pay for marbling,” says Nina.

At the Renardsfält farm, they will try to reach half of that MBS, with a marbling grade at around 5-7. That will satisfy Nordic consumers, who John believes are not yet ready for the 12 grade which Japanese Black Wagyu breeders are aiming for. That meat has a fat content of around 50%. “A Swedish consumer would just pass beef like that.”