“We’ve managed to produce an organic protein concentrate from grass, clover and alfalfa with a raw protein content of 50-60% that we can substitute for soya-meal (46%) on a one-to-one-basis,” says Vagn Hundeboell, managing director of BioRefine. He runs the company’s production facilities set up in Varde on the Danish western island of Jutland. BioRefine is jointly owned by the three Danish ag groups DLG (50%), Danish Agro (25%) and DLF (25%).

Mr Hundeboell has a long personal history of extracting protein from alfalfa and similar crops. “I started working with this in the 1980s within the DLG group, but the time wasn´t right and we had tough global competition, so I went into the field of logistics and supply chains. But when this chance came up, I did not want to miss it,” Mr Hundeboell recalls.

Search for alternative protein sources

The pressure on European feed producers and especially organic livestock farms to come up with alternatives to imported soya – which is not widely produced in Europe – has increased in recent years. This has added to the incentives to find domestically produced protein sources. So, in 2019 BioRefine was created and last year it acquired and remodelled an old feed plant in Varde, where it started up trial production. “Last year (2021) we produced a couple of hundred tonnes of our protein concentrate,” says Mr Hundeboell.

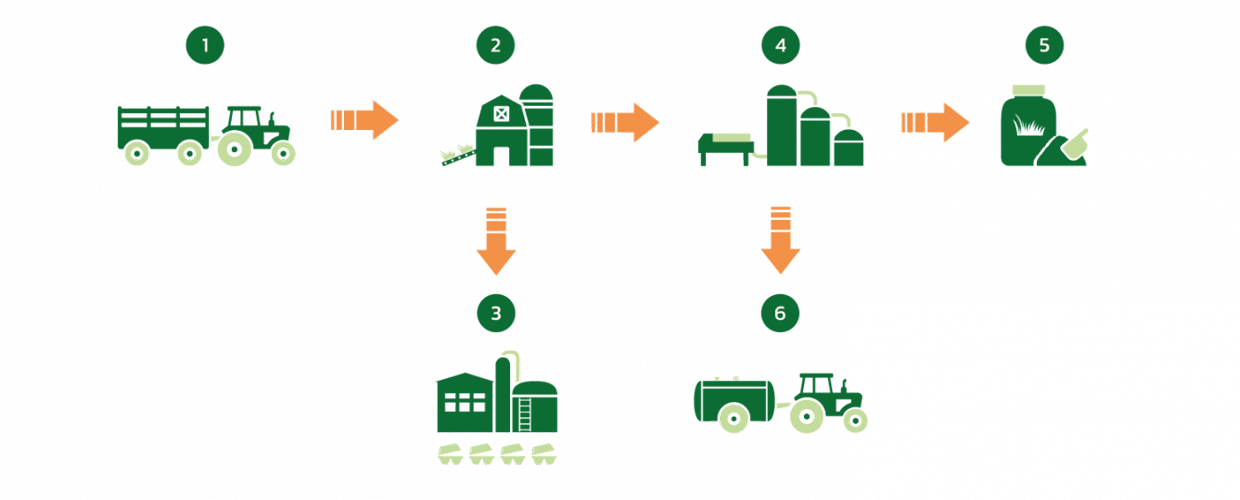

The production is based on established bio-refinery technology – but without the advances in modern biological research it would not have been such an easy task. The process relies on freshly cut grass from a specific seed mix. Within a few hours, the finished protein concentrate, which has a texture similar to ground coffee, is ready to be shipped to feed producers for feed compound production.

Fast harvest and further processing to avoid protein loss

In Denmark, grass reaches its highest protein content in early May, red clover at the end of May, white clover at the beginning of June and alfalfa at the end of June. “Tailoring our seed mixes to that helps to maintain good quality raw material throughout the season,” Mr Hundeboell explains.

Timing is of the essence here and it contrasts starkly with the much less time-sensitive grain production that it is partly expected to replace. Contracted farmers are responsible for seeding and crop management during the growing season, but BioRefine takes care of the harvesting with a well-organised logistics chain from field to production plant. This ensures a time-sensitive harvest in the best possible condition. “You have to have a quick production process, otherwise you risk losing too much of the protein,” explains Mr Hundeboell. “After 13-14 hours you may have lost some 40% of the protein.”

From some hundreds of tonnes produced in 2021 from roughly 500ha, Mr Hundeboell expects BioRefine to increase production this year to 7,000t from contracted farmers cultivating about 3,000ha. The goal, however, is set much higher. Denmark imports about 2m tonnes of soya-meal per year, of which roughly 70,000t are organic. And to replace that amount of organic imports with domestically-grown protein is realistic, he says. “It will take some acreage from grain farming, but not in any substantial way,” he adds.

Hover over the numbers to learn more about the production steps. (Source: BioRefine)

The grower’s perspective

While organic food products have struggled at times in the consumer market, the production method is gaining a foothold as a more sustainable way of farming. In Denmark, organic food has achieved an impressive market share in some niches. Organic eggs, for example, account for 40% of the market and milk, some 33%. The number of organic pigs is stable at around 460,000.

Mr Hundeboell agrees BioRefine will have to offer growers comparable or better income for taking deliveries from their contracted farmers compared to grain crops. In addition growers must meet the required specification, mainly concerning protein content. “We aim for a protein content of 20% but we can accept it from 18 to 22%,” says Nils Erik Nielsen, a farmer based in Vard on the west coast of the island of Jutland, who worked with BioRefine in 2021.

Mr Nielsen runs an organic farm of 70ha, comprising 20ha of oats or barley and 50ha of grass. “It has worked well so far and I have no complaints. BioRefine cut the grass promptly when the weather allowed,” Mr Nielsen says. He had hardly any problems with the crop: “As soon as it had established it developed very well and we reached an acceptable protein content and a relatively good yield. We’re paid according to dry matter and protein content. Although you would like to be paid as much as possible, I am ok with the payment I received in 2021.”

During a good year, BioRefine hopes to be able to cut the grass at Mr Nielsen’s and other participating farmers’ farms five times during a season. If alfalfa is in the seed mix, it aims for four cuts.

Spread the technology

Production of a premium protein concentrate that matches the qualities of soya, could create a business opportunity for BioRefine and its stakeholders. But it was never intended that its knowledge should remain the exclusive property of BioRefine, according to Morten Bye-Jensen, researcher at the Department of Biological and Chemical Engineering at Aarhus University. “There was a lot of talk among the Danish partners that we would not hide our experiences. We need to learn from each other, so we want it to stay open.”

Researchers at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) took a different approach to the technique and carried out trials on six-to-12 weeks-old weaners at the Sötåsen Farm School. Instead of using fresh-cut grass, they used juice from grass silage, producing a protein powder. “We reduced the protein from conventional feed sources by 10% and replaced it by with grass protein,” says Anna Wallenbeck, livestock production lecturer at SLU. “So, if the juice didn’t add anything to the feed, the weaners should have performed worse than the control group, but they didn´t. They grew as fast and some even faster.” Dr Wallenbeck says the trials at Sötåsen farm school will continue, with machines and equipment for producing the final protein powder purchased for further development.

“We have some 1m ha of cultivated farmland in Sweden,” says Christel Cederberg, professor in advanced energy at Sweden´s Chalmers University of Technology. “Producing green protein on some 100,000ha would not be impossible and we would have a good carbon sink source. This project has a double aim; to offer farmers the possibility to grow and use a domestically produced feed as an input, and to create a protein product for organic producers that fits into a circular agricultural economy. We´re just at the beginning of what we can do,” she adds.

On the way to more sustainability

Mr Hundeboell agrees the environmental benefits are important, especially as Denmark has struggled to meet the EU Water Directive requirements. Perennial crops are better at retaining soil carbon and will also reduce run-off from farmland. So far, in Denmark, the protein concentrate has been used in feed for egg production, resulting in a more yellow, appetising-looking yolk.

In pigs, trials have been showing good results, according to Mr Bye-Jensen, with equally matched growth and health to control groups, and no adverse effects on the eating qualities of the pig meat.

And with rising feed costs as organic soyabeans become scarcer, finding an alternative to these imports has become increasingly important. In December 2021, soyabeans were trading at $12.60/bushel on the Chicago exchange, and organic soya costs twice that.

“We find it more and more difficult to buy organic soyabeans and we have to look at exotic markets like China and Kazakhstan, sometimes Romania,” says Mr Hundeboell. He envisions BioRefine’s protein concentrate could match conventional soya, especially if all the environmental benefits are taken into consideration.

As the production also creates large volumes of green fibre-mass, a market for this product is vital, economically. Currently it is used for bio-energy production, but BioRefine hopes to be able to produce other products such as textiles and packaging.

“We are currently co-operating with a Swedish egg producer, making their egg packages,” says Mr Hundboell. “This could replace the use of paper and you could return it directly back to the fields. It´s grass!”

BioRefine´s Seed Mixes

Mix 1

- Perennial ryegrass (bovina): 25%

- White clover: 20%

- Rajsvningel, a cross-bred between meadow-fescue and Italian/English ryegrass: 25%

- Ryegrass (fabiola): 30%

Mix 2

- Ryegrass (fabiola): 30%

- White clover: 20%

- Ryegrass (bovini): 25%

- Rajsvingel: 25%

Mix 3

- Rajsvingel: 30%

- Rajsvingel (fojtan): 20%

- Ryegrass (bovini): 13%

- Red clover: 17%

- White clover: 10%

Mix 4

- Alfalfa: 50%

- Lucerne: 50%