A self-propelled machine that steers itself across the fields, harvests solar energy and a H2 harvesting system that converts it into hydrogen. That is the idea behind the H2arvester (for hydrogen harvester), the first prototype of which was tested last year in the Netherlands. “We were looking for new ways to combine energy and agricultural production,” says co-initiator Wouter Veefkind. “In this respect, multifunctional land use is of great importance.”

Wouter Veefkind, co-initiator of the project H2arvester

Production of H2 by electrolysis

This is where the H2arvester comes in. In 2017, this innovation was awarded a sustainability award by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate. Since the prototype has been in the field, interest has picked up. “There is a lot of interest from the market,” says Mr Veefkind. “On the one hand, it is a policy solution as a response to the solar parks. That’s why there is now a certain urgency; we need a proof-of-concept.” This year there will start a trial at a strip cultivation plot at the ‘Farm of the future’ of the Wageningen University & Research.

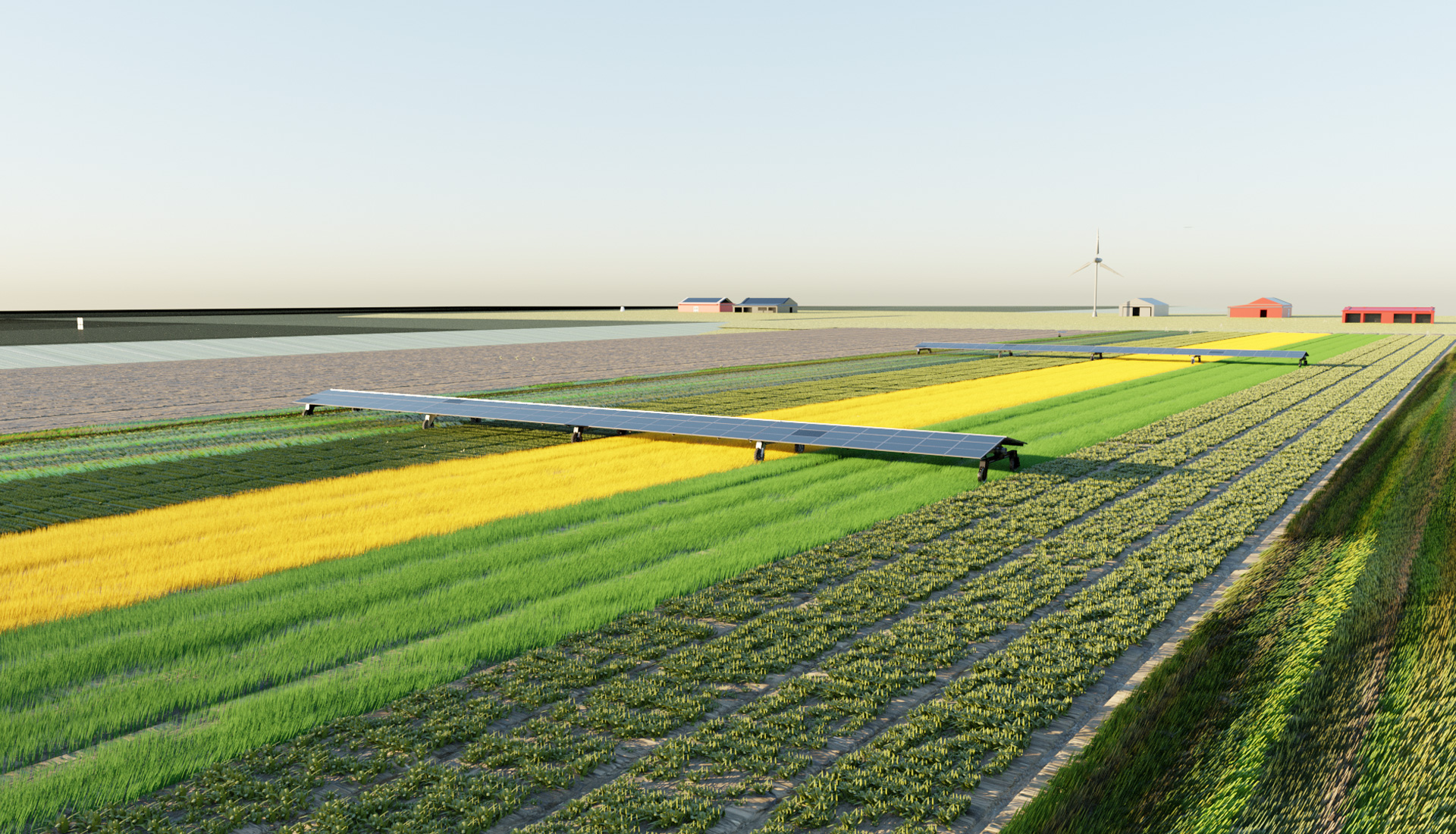

The harvesters are composed of solar panel segments supported by motorised wheelsets, which allow them to move autonomously on arable fields and grassland; even getting across ditches, as former trials revealed. The idea here is to achieve double land use; the maximum surface covered by the moving panels would amount to 10% of the field. The yield from the solar panels is then used to produce H2 via electrolysis, the process of using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. H2 could be stored on house lot of the farm and could be used to be self-sufficient or to share it with a co-operative organisation.

From 2022, the prototype “H2arvester” will be tested at the Dutch University of Wageningen.

After storage H2 can be used to produce electricity by fuel cells. “However this is from an energetically point of view, unprofitable”, says his companion Marcel Vroom. “It would be better to apply H2 directly as fuel for transport, mechanisation and heating. Storage of H2 and the collected solar energy are also meant to use as seasonal storage by which the farm could function energy neutral.

The next step would be to use this technology during cultivation, so that it generates energy and can carry an implement.

Wouter Veefkind

The stacks that are needed for electrolysis, are getting developed. Mr. Vroom explains: “The prototype has proven itself technically. Now, we need a viable plan. Our system is often compared to solar panels on the roof and in terms of pricing, we are in a higher bracket. However in the Netherlands, the H2arvester is seen as an agricultural applications, so we can apply for subsidies concerning agricultural applications as soon as 2023.“ He emphasizes that H2arvester is more than only ‘mobile sun on land’. „It stands for a chain of sustainable energy solutions. Therefore we are looking for partners and investors to jump into the role of chain director. That’s why we need to a proof of concept too.“

Win-win

“The agri-industry needs to bring down its CO2 footprint and, in that light, invest in sustainable electricity,” Mr. Vroom adds. “That’s certainly the case when it comes to logistics; lorries, for example, will have to run on hydrogen in the future. So if a farmer makes their land available for such a technology, then they can supply hydrogen to their dairy farm, for example. That gives them a new revenue model and the dairy farm can operate in a more sustainable manner.”

Trucks will also run on hydrogen in the future.

Or think of an arable farmer who grows a dormant crop like a winter cereal. “At this time of year, the farmer has little income, so it would be great if they could generate more income by producing energy and selling it. In this way, you build a new chain together.”

Another advantage is that this way of generating energy does not put pressure on the existing electrical grid. “In the Netherlands, we are already facing an capacity problem in the network, so if the energy that is produced doesn’t have to be distributed on the electricity network, but can be converted into hydrogen that the farmers use themselves and suppliers can buy, then the network will not be burdened any further. It’s a win-win for both parties.”

Second track

The initiators are busy working out a second track. “The best thing would be if our innovation could also be used during cultivation, so that it generates energy and can carry an implement, for example,” says Mr Veefkind. “In arable farming, which is increasingly working with strip cultivation, that would certainly offer opportunities, but that is the next phase.” Mr Veefkind is feeling hopeful. “Bringing something new to the market is always a challenge, so we’ll just have to assume that’s part of the deal. Its about building an ecosystem. The future will tell if it is possible to sell green hydrogen at a premium.“

For more information:

- to the Dutch project H2arvester