Mr Beisel, you saw how the one millionth tractor came off the assembly line in Mannheim 30 years ago, and now also the two millionth. What has happened during this time period?

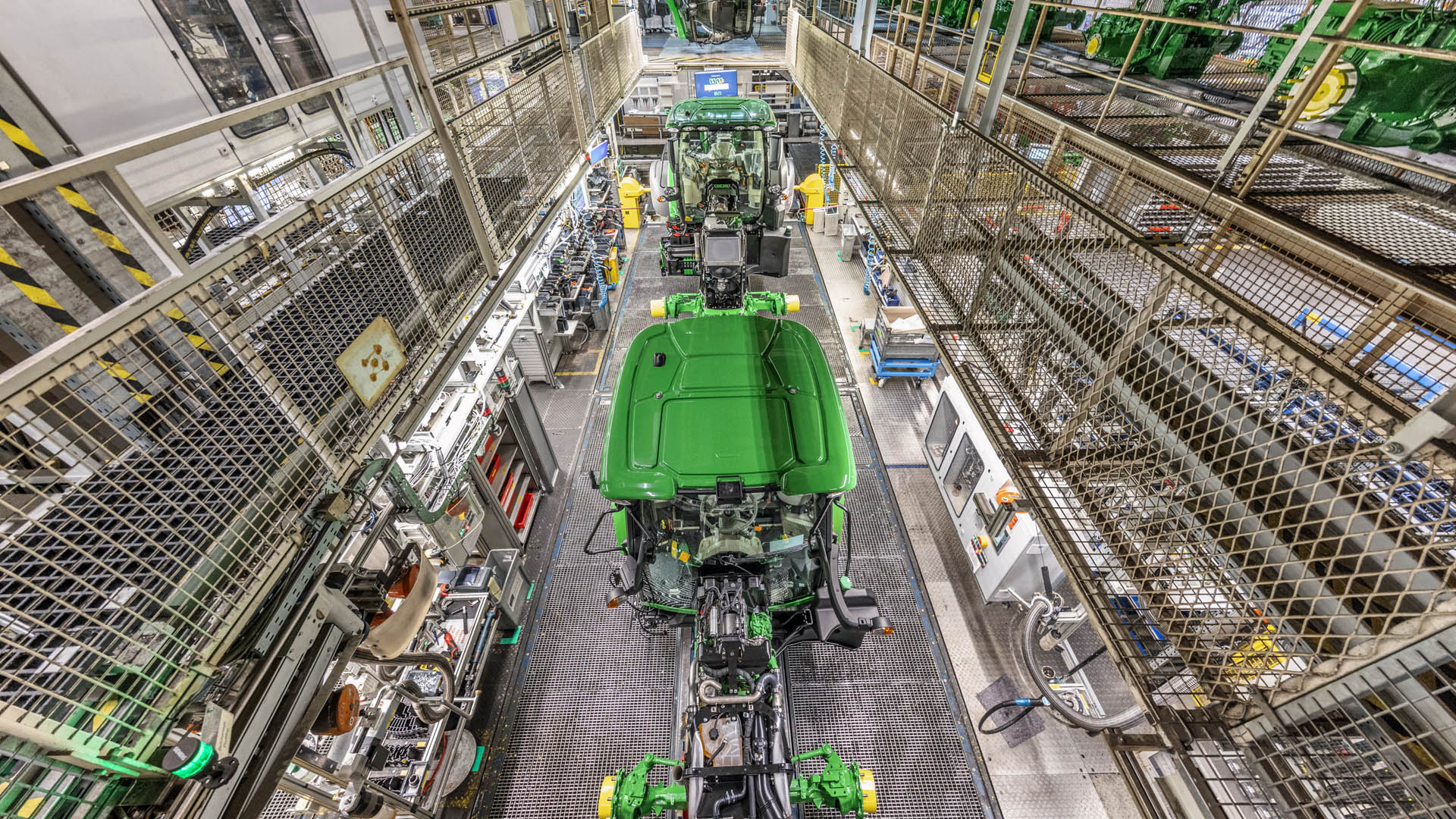

The first obvious change that comes to mind is the increased complexity of the tractors. At first, you could see from one end of the new tractor assembly line to the other. Today, there are boxes on the conveyor belt, and tools and equipment are hanging from the ceiling. Things look completely different; these are two different worlds. Thirty years ago, a tractor had almost no on-board electronics. There was a mechanical injection pump, and if it didn’t work, then you had to adjust the throttle cable, and everything would work once again.

In the 2000s, the tractor was completely (as I always say) electrified. We then came up with an electronic injection system. The speed control pedal was suddenly turned into a small potentiometer, which had to be installed. Then came the suspended front axle, and where there used to be two or three controllers, there are now six or even eight. Then there were all the electronic controls. The largest model now has 14 and sometimes even 16 controllers. Due to the high level of technical complexity and variety, many work steps are no longer possible directly on the main assembly line and have to be outsourced.

Can you give a specific example, from your work, that shows the extent of these changes?

One good example is the pre-assembly of the bonnets. That was one of my first tasks, after completing my training as an Industrial Mechanic in 1992. Back then, such a bonnet was made entirely of sheet metal, that is, without any plastic parts. I assembled a total of about 30 parts: the hinge there, two screws here, then a headlight grille with two headlights, the rubber seal and some linkage – and the job was done.

Today, in comparison, if I look at the bonnets of our larger tractors – there are 250 screws for these alone. The number of possible variants has also increased. There used to be a choice between two sets of light configurations, one for right-hand traffic and one for left-hand traffic. Today we have low beams, high beams, LEDs, no LEDs, and all of that for right-hand and left-hand traffic. A lot has happened there. The work requirement has also been continuously optimised and condensed.

How do you manage when it comes to mastering this complexity at work?

We worked our way up – step by step. One big advantage of our factory is that we have many employees, who have been with us for a very long time. The workforce has grown with the factory and can contribute all their experience to meet any challenge. Over time, they’ve learned all this complexity, without realising it. In addition, we now have a lot of automated support in production and there are more people in each group, working in teams, than before. This is necessary to fulfill the orders we have, as quickly and reliably as we always do.

What role does automation play?

Today many areas of the factory are extremely automated. Particularly in parts production, robots are used to automatically load milling machines or lathes. There is also more automation at the final assembly: we used to screw the frame together by hand in jigs. Today we have a robot in the screwing station.

So, we employees get more and more support, which also improves the ergonomics of the process. Automation should be an assistant, that is, always working in the interests of the employees. They bring all the know-how with them every day, and I would like to continue working with them in the future.

What have been the greatest highlights for you, personally, over the decades?

I thought it was great when the factory was opened to visitors. We didn’t have that in the past. This was a positive development – that we became more open to the outside world. I grew up close to the plant, and before starting my apprenticeship, I had almost no idea of what was happening behind the red brick walls. Today, people from the area know the company much better, and immediately, positively, recognise the brand when I tell them that I work for John Deere.

Another highlight was how we dealt with a tyre delivery shortage. We couldn’t afford not to build tractors, waiting until tyres were reliably supplied again. And so we built 800 tractors without tyres, we fitted them with tyres later on. This allowed us to prevent a production standstill, despite the delivery bottleneck. Our motto is: If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t exist.

How would you summarise your 35 years with John Deere?

All in all, I can say that at John Deere I was able to grow from a trainee to a manager, while at the same time watching the plant grow. That’s a good feeling.