The buildings of the 37 hectare test field are getting a bit old. On the wall hangs a black and white portrait of the founder of the agricultural trials. Dr Julius Kühn died in 1910 and has, since 2008, been the namesake of today’s Federal Research Centre for Cultivated Plants (JKI), based in Quedlinburg.

Prof Dr Julius Kühn was one of the most important pioneers of applied agricultural science in the mid 19th century.

Dr Kühn, remembered as a pioneer, acquired the site, which at the time lay far outside of the city, with a view to giving his agriculture students a better understanding of both theory and practice, in the spirit of Humboldt’s universal teaching: Theory in lectures, practical study and experiments on live plants in the test plots.

This means his students, who had come to Halle from all corners of Europe, moved back and forth between the uni buildings and test fields. This was the mid 19th century, when agricultural science was completely unchartered territory. Whether or not, back in 1878, Dr Julius Kühn had set his sights on establishing 6,000m2 of multi-plot rye fields that would keep the experiment going into the 21st century is unclear, but that doesn’t change the fact that these rye plots have survived the First World War, the Nazis, the Second World War and and the fall of the Iron Curtain.

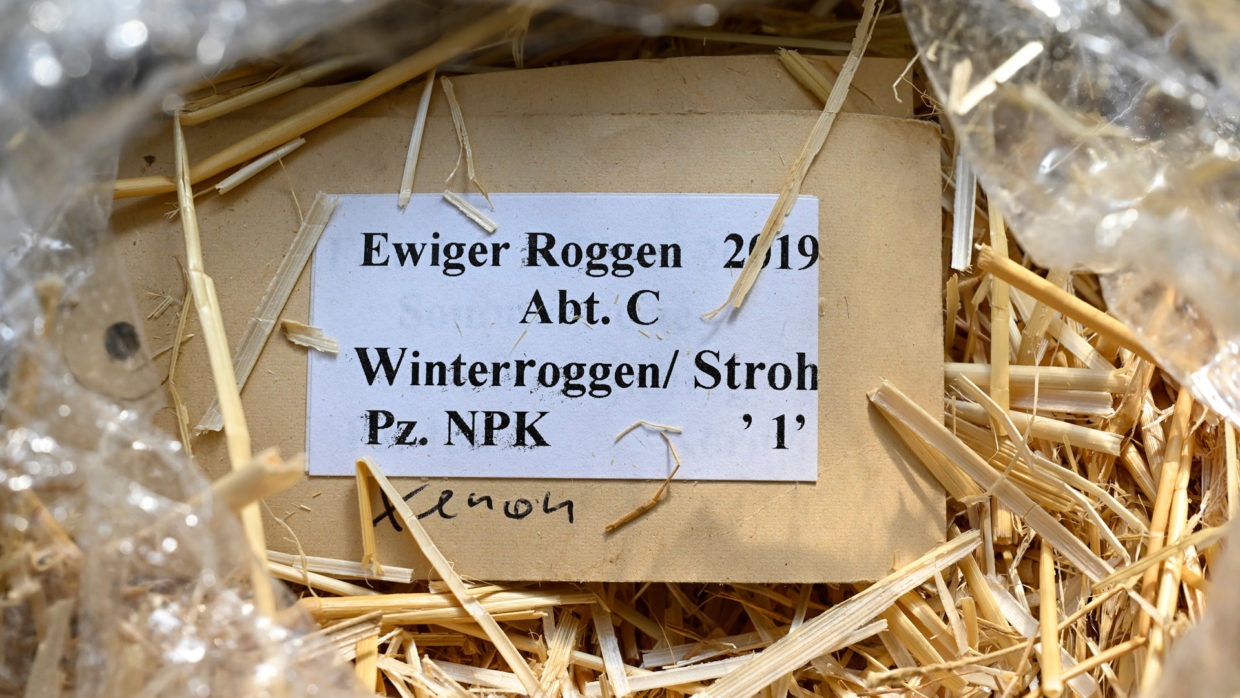

This means rye has been grown, uninterrupted, on the same site for an unbelievable 142 years. This is why it has been dubbed “Eternal Rye Cropping” in agricultural circles.

142 years of endurance testing

Station leader, Dr Helmut Eißner, walks along the narrow path that his famous predecessor, Dr Julius Kühn, probably also frequented in the mid 19th century. On the edge of the plot, only a few hundred metres further away, you can see Halle’s large depot. A few minutes’ walk from the administration building, he stands in front of the second oldest plant endurance experiment in the world. Only in Great Britain, at the Rothamsted Research institute, just north of London, are there endurance tests that are even older. “Here, we have five different variants of organic and mineral fertiliser and one unfertilised area,” he explains. While it is only the beginning of March and the winter rye has not yet been planted, the differences from plot to plot are fairly easy to see.

The results from the “Eternal Rye Cultivation” show that we can use our soils sustainably and productively in the long term. That works.

Dr Helmut Eißner

Halle’s endurance test continuum is remarkable. The long-term measurement data alone, such as harvest yields and soil samples from the respective endurance fertiliser tests, have great value in terms of explaining ecological change processes. If harvest yields are then compared with climate data, this endurance test provides valuable information about the correlation between the soil, the crop and the atmosphere. Even the correlation between plant compounds and the supply of nutrients in the soil was under scientific observation at this site for a long time. Today, however, this is not the case, as Dr Eißner, who has been responsible for the testing station since 2001, regretfully admits.

Even non-scientists recognise relatively quickly the importance Halle’s historic soil has for plant research. It represents a unique archive of the cultural history that has been afforded special protection by the state of Saxony-Anhalt since 2007 as a monument for “Eternal Rye Cropping”. However, there is a lack of financial resources to allow good research continue. To garner these resources, politicians and the research landscape must be galvanised, a feat which has, however, not always been achieved in the past, Dr Eißner concedes.

Nevertheless, it keeps going, says Dr Eißner, who is at the end of his long career, which he began with a degree in agriculture at Halle and will end supervising the test field at the University. In the eighties, he was promoted to soybean cultivation at the Leipzig Tropical Institute. He worked on endurance field tests in Santa Clara in Cuba and was in Nicaragua from 1990, where he also worked on experiments at the National University for Agriculture on the outskirts of the capital, Managua.

The soil never forgets

“As farmers, everything we do with the soil is also reflected in the harvests”, says the doctor of agricultural science, about the comparative fertilisation experiment. The plot that has never been fertilised still delivers a return of an extrapolated 1.5 – 1.7t/ha after almost 150 years of monocropping. “Whether or not we now fertilise organically or with minerals is relatively insignificant to the soil.” states Dr Eißner. “However, these returns were higher in dry years with manure fertilisation because the water retention ability of the soil increases with more organic fertilisers.”

Especially impressive in the Eternal Rye Cropping is the comparison between the unfertilised plots and a plot that was treated with manure from 1893 to 1953, but has not been fertilised since then. Although there has now been no organic fertilisation for almost 70 years, the effect of it is still palpable. “The return has been constant, at 0.5t/ha, across the unfertilised area for years,” reports Dr Eißner. “The soil has a very good memory,” he adds, looking critically into the future.

The generations after us will have to deal with the consequences of the current soil usage. “Ultimately, I learned what a responsibility it is to work with the soil here on the endurance trials fields,” says the 65 year old. Can badly treated soils be repaired? Dr Eißner is somewhat evasive. “We have no choice, no alternative. If we want to hold on to extensive agriculture in Germany, it must also be possible for us to put things right. The soil is repairable but it doesn’t even need to be damaged in the first place.”

Orientation for the future

All farmers certainly share this view. And therefore it would not only be preferable, but in fact absolutely necessary that “Eternal Rye Cropping” not only be continued as an orientation aid for agriculture, but potentially even broadened. The historical data on Eternal Rye Cropping provide important scientific input for discussions on all future questions about climate change and its effects on agricultural production.

“Achieving sustainable productivity”

Interview with Dr Helmut Eißner, head of the teaching and testing station at the University of Halle.

If we take a look into the future, will the long-term “Eternal Rye Crop” (Ewiger Roggenbau) trial still exist in 2050?

I am firmly convinced that the “Eternal Rye Crop” trial will always exist. Whether other long-term fertiliser trials will continue until then is debatable. If they indeed still exist, they are likely to instead be in the form of direct sowing trials, which dispense with tillage to avoid disrupting the soil.

What conclusions can agricultural researchers draw from the “Eternal Rye Crop” trial in relation to the anticipated change in climate?

Rye, as a C3 plant, is a good indicator of increasing CO2 levels in the atmosphere. By way of comparison, we also have corn in the trial, which, as a C4 plant, is a good indicator of temperature and drought resistance. At our low-absorption site (42 soil points), the interactions between soil and plants are particularly significant. Nevertheless, we must remain modest, because we cannot simply transfer the results from land parcels with an area of 2,000m2 to 2 million hectares of corn.

If the average temperature at the trial location increased by 2°C and the rainfall distribution remained at a similar level as today, would this have a positive effect on the rye?

If it turns out that global warming makes summers only slightly warmer but winters significantly warmer, it would be ok. However, all information indicates that winters will be wetter and summers will be drier. Therefore, growers are also working on varieties that are ripe by mid-June.

What research topics will be interesting for the future?

In Germany, we have been talking about agriculture almost exclusively in the context of extensification and environmental protection for over 20 years. But the main question is still productivity. This question is all the more pertinent if you know that many tropical soils cannot be used as productively and sustainably as those at our latitudes.

What insights does the “Eternal Rye Crop” trial offer you in this regard?

The findings of the “Eternal Rye Crop” trial do show, however, that we can productively and sustainably use our soils in the long term. It works. Both with mineral fertilisers as well as organic fertilisers.

Do you believe that sustainability and productivity are compatible?

It’s up to us whether or not they’re compatible. To achieve this, there is no doubt that we need circular-flow thinking and action that lasts for generations.